STUPIDITY AND SAVAGERY IN POWER: SCENES FROM MYANMAR IN CHAOS

Myanmar teaches us: being bad is not enough. It is not enough to drown any protest in blood, it is not enough to drive millions of people to hunger and despair, it is not enough to exploit, torture, enslave – and it is not enough to focus on smuggling. If something doesn’t work, a dictatorship doesn’t change it. It usually makes it worse, as more and more examples in human history show. But the leaders of the Tatmadaw, the ferocious Burmese army, don’t know these things – they belong to the same mould as the North Korean dictatorship. They were losing money (and not power), and they staged a coup that failed completely, as the people continued to rebel, and they were reduced to starvation – which is why, in recent weeks, there have been underground movements. If the dictatorship fails, then different choices must be made in order to save the Tatmadaw.

A year has passed since 1 February 2021, when the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military junta led by General Min Aung Hlaing, attacked Yangon, arrested Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint and hundreds of NLD leaders, then arbitrarily detained in unknown locations. Min Aung Hlaing proclaims himself Head of Government, and former General Myint Swe, who had been one of the two vice-presidents since 2016, is appointed interim president. Once again, a brutal season of bloodshed begins in this unfortunate country, with civilians paying the most.

The military onslaught generates a huge and unexpected whirlwind of protests across Myanmar. The security forces respond with astonishing ferocity: beatings, torture, rape, massacres: according to Human Rights Watch, 1,300 civilians were killed between 1 February and 1 December 2021. At least 75 of them were children, and more than 8,700 government officials, activists and journalists were arrested and tortured[1], 654 of whom were sentenced to severe imprisonment and 45, including two children, were sentenced to death[2]: these figures are approximate, given the difficulty of obtaining reliable information in a regime of total control of information.

The reasons for the coup are to be found in the fact that Myanmar was experiencing an economic boom, mirrored, however, by the economic crisis of the Tatmadaw (the Burmese professional army) and the companies linked to it – a situation that was leading to the soldiers no longer being able to be paid. The idea was that, by seizing power, this situation could be resolved. The opposite has happened: the chaos in the country, the hatred against the regime, the international sanctions and the pandemic have devastated the country: the International Monetary Fund estimates that Myanmar’s economy shrank, in a single year, by 17.9%[3]; the World Bank forecasts 1% growth in 2022, after years of positive results[4]; the International Labour Organisation (ILO) says employment contracted by around 6% in the second quarter of 2021, compared to the fourth quarter of 2020, with a loss of 1.2 million jobs[5].

Prices of basic necessities have soared unsustainably for the population, and in September 2021 the value of the kyat fell to 2200 per US dollar, the lowest level in history (it was 1330 on 1 February) [6], while average inflation rose to 7.%, even 9.8% for non-food items[7]; this has led to a contraction in trade (-15%, or 2.5 billion dollars) between July and December 2021, a drop in exports (-16%) and imports (-15%)[8]. The foreign trade balance is still positive ($228 million), but it is 45% less than the year before the coup[9]. As if that were not enough, the monsoons of July and August flooded the villages and property of more than 6 million people – a real disaster[10]. According to a United Nations analysis[11], soon 14.4 million people, including 5 million children, will need humanitarian aid to survive[12]. And just around the corner is the risk that foreign investors, who made the economic boom possible, will now abandon Myanmar.

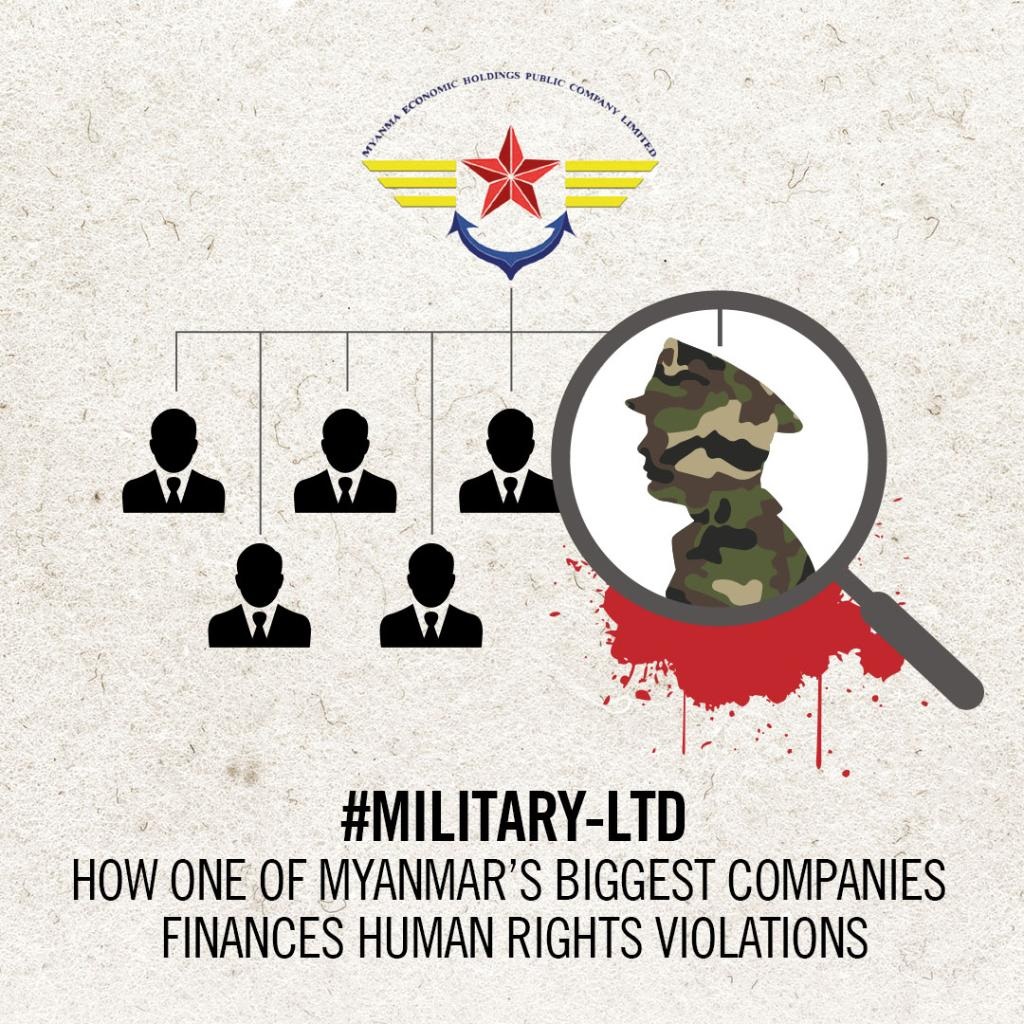

MEHL & MEC, the Tatmadaw’s holding companies

Amnesty International’s report on MEHL’s involvement with military repression[13]

The weakest point of Burma’s economic system is the fact that its biggest companies belong to the army[14]. The Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL) and the Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) control over a hundred companies: banking, commerce, logistics, construction, pharmaceuticals, insurance, mining, gas, tourism, agriculture, timber, palm oil and sugar production, soap, cement, tobacco, food and drink, and much more[15]. Even businesses that are controlled by smuggling, such as jade, directly or indirectly depend on the centralised leadership of these two military holdings[16].

Myanma Economic Holding Limited (MEHL) is the first private company to be established in Myanmar since the military coup in 1988, and has four main objectives: ‘the welfare of military personnel and their dependents, the welfare of war veterans, the welfare of the general public and the contribution to the economic development of Myanmar’. Over the years, MEHL has generated substantial profits for the Tatmadaw and its management, most of which are administered by the group’s bank, the Myawaddy Bank[17]. The Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) was set up in 1997 to “contribute to the Myanmar economy, meet the needs of the Tatmadaw, reduce defence expenditure and ensure the welfare of military personnel”: is active in the mining, manufacturing and telecommunications sectors, and owns Innwa Bank[18].

According to a UN report, the reason MEHL and MEC control the entire economy is because of its monopoly of the mining industry[19]. The two groups hold the licences to extract jade and ruby in the states of Kachin and Shan, which are vital for Burma’s exports[20], and all concessions for the exploitation of oil fields, forests and other mineral resources are controlled by the military[21]. These companies independently oversee the regulation of their respective sectors, collect and allocate revenues, license private companies, and operate commercial joint ventures without any external oversight, and Burmese law allows them to retain large profits outside the state budget and without accountability to anyone[22]: the report concludes that ‘these economic structures […] support the power and influence of the Tatmadaw, which continues to obstruct democracy and commit egregious crimes with impunity’[23].

Justice for Myanmar[24], a group of activists opposed to the regime, has published two documents that reveal how MEHL finances the military. The first, ‘Report on the Status of Shares and Dividends of Directorate Offices, and the Military Units under respective Regional Military Commands for the fiscal year 2010-2011’, was filed by MEHL with Myanmar’s Directorate of Investment and Corporate Administration (DICA) in January 2020. This states that MEHL is owned by 381,636 individual shareholders, all of whom are serving or retired military personnel, and 1,803 ‘institutional’ shareholders, consisting of ‘regional commands, divisions, battalions, troops, war veterans associations’[25]. The second document, “List of Original Shareholder Registry (50) Persons, Myanma Economic Holdings Limited, until (30-8-2019)”, is a confidential MEHL shareholder report covering the 2010-2011 fiscal year which, in addition to providing information on the identities of MEHL shareholders, documents the large annual dividend amounts received by the same shareholders between 1990 and 2011[26].

The documents unequivocally demonstrate how the huge profits are systematically and institutionally distributed among regiments, military units and military leadership: according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, the Burmese army has a force of 507,000 men, the air force 23,000 and the navy 19,000[27], all of whom are responsible for war crimes widely documented by the United Nations[28]. And if the MEHL and MEC bear these serious responsibilities, anyone doing business with these holdings can automatically be considered an accomplice to the crimes, as Amnesty International and NGOs fighting for democracy in Myanmar insist[29].

Investor flight

Burmese activists accuse energy companies of funding the Tatmadaw[30]

Immediately after the coup, economic sanctions against the regime were decided everywhere: the United States[31], Australia[32], New Zealand[33], Japan[34], the United Kingdom[35], South Korea[36], the European Union[37], Canada[38] and Switzerland[39]. Many private companies have withdrawn from the country: the logic expressed by Amnesty International that “if you do business with the Tatmadaw you are either an accomplice or a co-conspirator” is now recognised by the entire international community, and staying in Myanmar causes a clear loss of image – while other companies are withdrawing because of the crisis generated by the chaos in the country.

The NUG, the shadow government set up after the coup, is urging citizens to stop working with military companies[40]. The “Stop Buying Junta Business” campaign is launched[41] and, through social networks, several boycott actions are organised (such as #NoBusinesswithGenocide[42], #hearthevoicesofMyanmar, #CivilDisobedienceMovement[43], #rejectmilitarycoup[44], #saveMyanmar and #whathappeninginmyanmar[45], #savemyanmarfrommilitarycoup[46]), but the boycott is individual and generalised – as shown by the thousands of civil servants who stop going to their offices[47], the tens of thousands of students who stop using services, banks and businesses linked to the military[48], the campaigns of all the trade unions[49]. Burma Campaign UK publishes a list of brands and products linked to the military[50] and invites the international community to join the Burmese people and stop buying from these producers[51].

Foreign investors begin to react: one of the first withdrawals is announced in February by the Japanese beer giant, Kirin, which has a partnership with MEHL (and a controlling stake of $1.7 billion) in Myanmar Brewery – a company that came under indictment in 2018 for admitting to having made three donations to the army totalling $30,000 between 1 September and 3 October 2017, at the height of the ethnic cleansing campaign against the Rohingya population in Rakhine State[52]. Kirin is unsuccessful in its efforts to dissolve the joint venture with MEHL as the government opposes it, forcing the Japanese to choose the path of arbitration[53]. Surprisingly, in January this year, the Yangon court rejected a MEHL complaint seeking to seize Kirin’s shares in Myanmar Brewery, referring the decision to arbitration[54].

The Kirin case is the litmus test that shows the Burmese people how effective protest can be. As a result of the boycott, Kirin is suffering heavy losses: Myanmar Brewery’s operating profit, from January to March 2021, is down 49.6% compared to the same period in 2020 – 2.5 billion yen (almost $23 million); revenue will also fall by 46%, or 5 billion yen (almost $46 million) less[55]. If Kirin, from a spectacular point of view, is the greatest success of the protest, in fact it is the energy sector that suffers the most: according to Human Rights Watch, natural gas projects in Myanmar generate more than $1 billion in revenue for the junta every year[56], and according to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative they are Myanmar’s main source of foreign exchange revenue, 4.8% of GDP, 5.2% of tax revenue and 35% of total exports[57].

Myanmar Brewery employees call for boycott of their beer[58]

All the extractive industries in Myanmar are under the MOGE (Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise), 100% state-controlled (i.e. the Armed Forces), which is involved in four offshore gas projects[59]: Yadana (operated by TotalEnergies and Chevron), Shwe (operated by POSCO International), Zawtika (operated by PTTEP) and Yetagun (operated by Petronas, but currently suspended for technical reasons[60]). 80% of the gas produced is exported to Thailand and China[61]. Until the day of the coup, Myanmar was earning $1.5 billion in tax revenues per year[62].

The NGO EarthRights International[63] accuses Total and Chevron of covering up human rights violations by the Burmese army, and claims that US$ 4.8 billion of gas revenues have been siphoned off from state budgets and ended up in personal accounts in two banks in Singapore[64]. The two companies, after much prevarication, announced their withdrawal from Myanmar[65]. The Australian energy giant Woodside Petroleum, under pressure from human rights groups, announced its intention to withdraw[66] from Myanmar in January 2022[67]. Woodside extracts gas from the sea, and is accused of paying millions of dollars to the junta[68].

The termination of the contract concerns the A-7 offshore block, of which Woodside owns 45% and Shell 45%[69]. The company also says it will withdraw from three other offshore fields, giving up $209 million a year[70]. Shell, Woodside’s partner in Myanmar, gave up its licences as early as 2020[71]. On 21 January 2022, KBC Kanbawza Group of Companies also announced the dissolution of its subsidiary Nilar Yoma Gems Co. Ltd, which operated a jade mine in the Sagaing region for years with MEHL[72]. KBC is among the companies accused by the United Nations[73] of financing the construction of a barrier along the Myanmar-Bangladesh border to prevent the displaced Rohingya population from returning home[74].

The exodus involves a myriad of companies from every sector: Germany’s Metro[75], Britain’s British American Tobacco (BAT)[76], Norway’s Telenor Group[77], America’s McKinsey & Company and Coca-Cola[78], and France’s EDF[79] and Voltalia[80]. Sweden’s Hennes & Mauritz (H&M) and Italy’s Benetton Group Srl stopped buying from local producers, throwing the entire textile sector into crisis[81]. Thai real estate group Amata suspends one of its major construction projects in Yangon, and Suzuki Motor’s two factories close[82]. Meta Platforms Inc (Facebook Group), bans all activities controlled by the Myanmar military from accessing its platforms[83], while Alphabet Inc (YouTube) removes five military-run channels from its platform[84].

Rothmans Myanmar Holdings Singapore (RMHS), a Singapore-based tobacco company that has been operating in Myanmar since 1993, shuts down in January 2021, shortly before the coup, and sues MEHL because it forces the shareholder to make monthly donations to a fund for disabled veterans that the Tatmadaw probably uses for other purposes[85]. And the list goes on, obviously including commercial trading companies, and dozens of small and medium-sized enterprises.

Those who don’t give up business with the Tatmadaw

One of South Korea’s POSCO natural gas extraction sites in Myanmar[86]

While a number of international companies have already fled Myanmar or are in the process of leaving, South Korea’s POSCO Coated & Colour Steel Co., a steel products company and the world’s fifth largest steel producer[87], continues to invest in the important Shwe and Shwe Phyu offshore natural gas project undisturbed[88]. POSCO International owns a 51% stake in the Shwe natural gas project, and is investing $473 million in Phase 2 of the project (drilling a total of eight wells in the Shwe and Shwe Phyu gas fields) and $315 million in Phase 3 (building and installing a gas compression platform) [89]. POSCO also invests in tourism and builds, on land owned by the Tatmadaw, a 15-storey 343-room luxury hotel, a 29-storey 315-room apartment hotel, plus other facilities including a conference centre, some restaurants and a swimming pool[90], and pays a substantial rent directly to the Ministry of Defence[91].

Despite POSCO stating in late May 2021 that it would suspend profit-sharing with MOGE[92] and buy back the 30% stake in its Burmese subsidiary owned by MEHL[93], nothing has happened to date. On the contrary, according to Myanmar Now, not only does POSCO have no intention of revising its corporate structure, but it even plans to increase its South Korean workforce by adding staff[94]. In November 2020, two South Korean activist groups, Korean Civil Society in Solidarity with the Rohingya (KCSSR) and Korean Transnational Corporations Watch (KTCW), together with Justice For Myanmar activists, filed a complaint with the United Nations and Korea’s human rights watchdog against POSCO and other companies (Pan-Pacific and Inno Group) that continue to have partnerships with MEHL[95].

Apart from this, while most countries have suspended arms sales to the Burmese regime, Italy continues to supply helicopters, which are used in the civil war against rebels hostile to the regime[96], and collaborate in support of military drones sold to the Burmese air force by the Israeli group Star Sapphir[97]. Of course, these nations are no exception in the tug-of-war between the West, Islam, China and Russia in the new century. For them, the Myanmar coup and the decision of many countries to break off industrial relations with the Yangon dictatorship is a great opportunity, and they are trying to exploit it to the full.

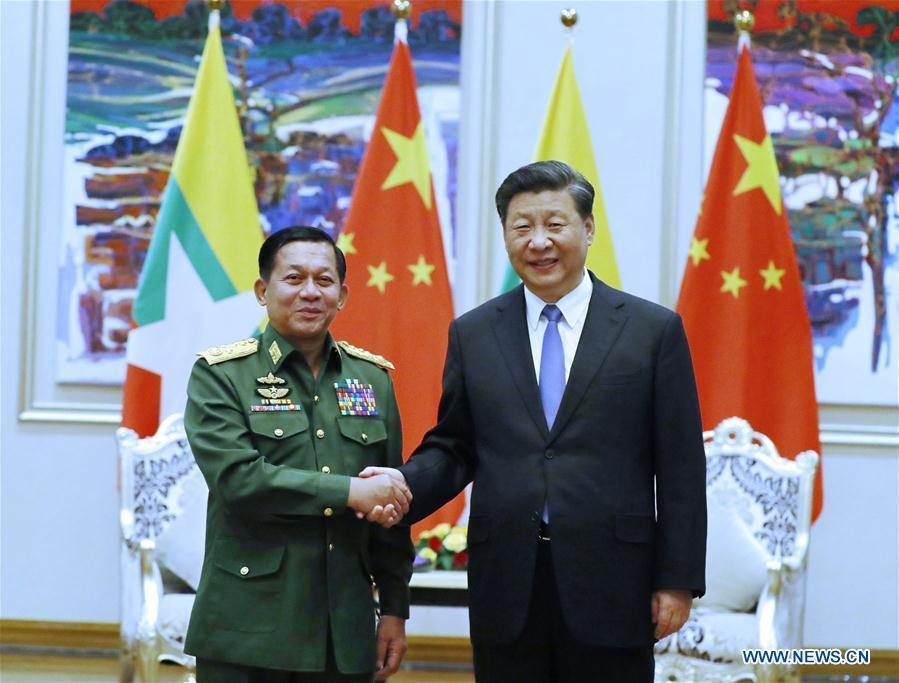

China is close, Russia too

President Xi Jinping meets with Myanmar Defence Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing[98]

Beijing is Myanmar’s main trading partner: in 2019, bilateral trade amounts to about $12 billion out of a total trade of about $36 billion, so as much as a third of Burma’s entire import/export[99]. China supplies machinery, vehicles and telecommunications equipment, while importing large quantities of tin, other minerals and energy from Myanmar (oil and gas account for more than 32% of total exports[100]). China is also dependent on Myanmar’s rice, whose imports have grown from 100,000 to half a million tonnes over the past decade[101]. In return, it builds oil and gas pipelines, oil terminals, hydroelectric, coal and renewable energy plants[102], all of which, like the development of an offshore port in Kyaukphyu for USD 1.3 billion, as part of the Belt and Road project[103].

China’s involvement in the mining sector is a real boon for the military junta: the Chinese mines of Lapadaung, Sapetaung and Kyesintaung and Tagaung Taung have brought $725 million into the coffers of the Tatmadaw by 2020/21[104]. And then there are the weapons[105]:: $1.3 billion between 2010 and 2019, or 50% of Burma’s armament in radars, warships, combat and training aircraft, armed drones, armoured vehicles, missiles and transport vehicles[106]. The coup did not change anything: on 20 December 2021 a Chinese-made submarine UMS Minye Kyaw Htin Type 035[107] entered the Malacca Strait, headed for the Indian Ocean and on 23 December entered the Yangon River in Myanmar, officially entering service for the Burmese Navy[108]. According to China, this also helps the population, as it contributes to the stability of the system[109]. In reality, Chinese investments are part of the geopolitical project to encircle India, which, for Beijing, is growing too fast[110].

Also Moscow, after the coup d’état, has intensified relations with Myanmar: the list of bilateral exchanges, including trips, symposia, conferences, formal and informal meetings, public or confidential, all strictly on military matters and involving ministers and high officials of the respective armies, is very long[111]. On 22 June 2021 (four days after the resolution issued by the UN General Assembly calling on the 193 UN member states to stop the flow of arms to Myanmar, which Russia has not signed[112]), the Commander of the Tatmadaw, Min Aung Hlaing, and the Russian Defence Minister, Sergei Shoigu, agreed in Moscow on the “prospects for developing bilateral cooperation, especially in the military-technical sphere”[113].

Russia is Myanmar’s second largest arms supplier after China, and is also involved in the education and training of its military[114]: Su-30 fighter planes, Yak-130 training planes, Mi-24, Mi-35 and Mi-17 helicopters, and Pechora-2 surface-to-air missiles[115]. For Yangon to pay, on 27 October, General Min Aung Hlaing meets leaders of the Russia-Myanmar Association for Friendship and Cooperation to discuss investment and cooperation in the production of fuel, natural gas, cement, fertilisers, steel, electricity and public electric transport, tourism, health, education, culture and air traffic management between the two countries[116].

Japan, for example, condemns the coup (belatedly[117]), but does not subscribe to economic sanctions and, on the contrary, tries to normalise relations with the new regime[118]. Japan has long been involved in Myanmar: from 2012 until 2015 Tokyo waives most of the debt owed by the former Burma (303 billion Yen), provides a 200 billion Yen bridging loan to allow Myanmar to settle its arrears with the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, oversees the creation of the Yangon Stock Exchange, and agrees to set up the Thilawa Special Economic Zone, of which it controls 49% and which finances the development of small and medium-sized enterprises, port infrastructure and the transport network[119] with Mitsubishi, Marubeni and Sumitomo, with a subsidised loan of 43 billion Yen[120]. About 70% of the 700 Japanese companies operating in Myanmar[121] are maintaining or expanding their activities despite the situation[122].

The secret jade market

The jade quarries in Hpakant produce inestimable wealth, much of which ends up in the smuggling routes and pockets of the Tatmadaw[123]

But this is not enough to prevent economic collapse, and the Tatmadaw should have calculated this from the start. It didn’t, because it has an ace up its sleeve: jade mines. Kachin State, in northern Myanmar, is home to the richest mines in the world[124]: a vicious circle of exploitation, smuggling and corruption that, according to Global Witness, allows China to import between 50% and 80% of Kachin jade illegally[125]. When, in 2016, the government of Htin Kyaw, the first one not in military hands, attempted a reform, suspending all mining licences, it had the opposite effect, pushing the army and rebel militias to extract jade faster and more dangerously than before[126]. The MEHL, which previously owned the vast majority of the mining licences and had left some to rebel groups[127], has all of them after the coup in 2021, yet smuggling is increasing: it is estimated that 90% of the precious stones extracted in Hpakant, for example, are sold on the black market[128].

The Tatmadaw didn’t see this coming: the Wa State Army (UWSA) has become a key trader in Hpakant, as has the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), and for the Arakan Army (AA), jade smuggling is what allows it to rise: most of the proceeds go into arms supplies[129]. Naturally, the Tatmadaw reacts violently in an attempt to wrest control of these areas from the rebels[130]. Global Witness calls the jade economy the ‘greatest robbery of natural resources in modern history’[131]. Jade mines have obliterated lush forests, replacing them with bleak landscapes of desert and dust, whole mountains transformed into huge quarries where hundreds of miners smash stones[132]. Many improvised miners rummage through the waste in the hope of easy money, on steep and dangerous slopes where they often meet their deaths[133]. In Mogok, in the Mandalay region, where an estimated 90 percent of the country’s gemstone extraction takes place, the MEHL companies have given way to local residents who manually extract the precious stones and are systematically looted by the Tatmadaw[134].

Once extracted, the jade ends up in Thailand, the world centre of precious stone processing, where a grey and well-tested system allows illicit trade to take place in complete safety[135]. The stones are then distributed to multinationals in the industry such as Graff, Van Cleef & Arpels and Pragnell, or to auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s, or to major retailers such as Walmart and Intercolor[136]. Obviously, buyers have no way (or perhaps interest) in tracing their provenance: of the more than 30 international jewellers, auction houses and retailers Global Witness interviewed, most said they had no control system in place to determine the origin of the jade they bought[137].

Civil war with an unpredictable winner

Civil war triggered by People’s Defence Forces triggers violent Tatmadaw reprisals against civilians[138]

The previous government is to blame. Aung San Suu Kyi, a former freedom heroine, prosecuted the genocide of the Rohingya people and did nothing to decrease corruption, continuing (and had to, in a compromise government) to support the Tatmadaw. The National Unity Government (NUG), made up of members of the National League for Democracy (NLD) who had won the 2020 elections, formed a sort of shadow government[139] branded as a terrorist group by the new junta[140] and failed to find a way either for an alternative project or for a compromise solution.

In May 2021, the NUG created an armed wing called the Popular Defence Forces, which collaborated with various rebel groups, supplying weapons, fuel, food and medicine, in the hope of regaining the trust of those who had felt betrayed by the NLD[141]. On 7th September, the NUG declared a “war of resistance” against Min Aung Hlaing’s regime, convincing elements of the Tatmadaw to defect (it seems that by November 2021, more than 2,000 elements had already defected[142]) and trying to improve its logistical organisation[143]. Alliance For Democratic Myanmar claims that the resistance army is made up of around 40,000 units, to which must be added those of the Sagaing region, which could reach 20,000 – plus a vast network of militias from numerous ethnic groups[144].

The idea of being able to counter an enormous military power like that of the Tatmadaw, composed of at least 350,000 units and among the best equipped in Asia, is truly ambitious. Mahn Win Khaing Than, Prime Minister of the NUG, says that he is convinced of winning the war within the year, but his words are pure propaganda[145]. It is true that the Tatmadaw is going through a very difficult phase, with a lack of resources, defections and losses in recent battles[146]. There is no doubt that a revolutionary process has been triggered, even though the Tatmadaw is spreading panic, destroying houses and looting villages considered hostile[147]. This complicates the position of Aung San Suu Kyi, who is confined to a secret location in the capital and who, to date, has collected numerous charges, some of which have been fabricated, and who risks spending the rest of her days in prison[148].

Aung San Suu Kyi, who was sentenced on 6 December to four years in prison for incitement to rebellion, was found guilty on 10 December of importing and illegally possessing walkie-talkies[149]. However, she was still facing a series of trials for at least 16 crimes she is alleged to have committed, including violation of the Official Secrets Act, corruption and abuse of authority in connection with real estate deals and the purchase and use of helicopters from the National Disaster Management Fund[150]. These are all charges that, if confirmed, could result in a 160-year prison sentence[151]. The United States reacted by blacklisting Attorney General Thida Oo, Chief Justice Tun Tun Oo and Chairman of the Anti-Corruption Commission Tin Oo[152].

The Tatmadaw appears as fragile as ever, but the NLD has deeply lost credibility. Much may depend on its international partners (Russia, Japan, China, Thailand, Singapore), but the year that has passed since the coup has shown that they are above all looking after their own interests. In this situation of converging crises, the search for an agreement between the LND and the Tatmadaw is on the horizon. Whatever it may be, it will solve nothing. And the regime has now realised that it has led the country to collapse. Either there will be an external solution, in the form of Chinese tanks; or a decades-long guerrilla war that will catapult the Burmese back into the Middle Ages; or a compromise that will bring back a sham democracy and, more importantly, the money that has now taken other paths. You can make a deal with a murderer, but it is better not to make a deal with an incompetent one.

JPN010

[1] https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2022/01/World%20Report%202022%20web%20pdf_0.pdf

[2] https://aappb.org/?lang=en

[3] https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/1/28/myanmar-lost-1-6-million-jobs-in-2021-amid-covid-coup-ilo

[4] https://money.usnews.com/investing/news/articles/2022-01-28/myanmar-economy-to-remain-severely-tested-by-coup-fallout-world-bank

[5] https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_814686/lang–en/index.htm

[6] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/kyat-09172021184904.html

[7] https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/c3299fac4f879379513b05eaf0e2b084-0070012022/original/World-Bank-Myanmar-Economic-Monitor-Jan-22.pdf “Myanmar Economic Monitor Jan 2022” – World Bank Group.

[8] https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/c3299fac4f879379513b05eaf0e2b084-0070012022/original/World-Bank-Myanmar-Economic-Monitor-Jan-22.pdf “Myanmar Economic Monitor Jan 2022” – World Bank Group.

[9] https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/c3299fac4f879379513b05eaf0e2b084-0070012022/original/World-Bank-Myanmar-Economic-Monitor-Jan-22.pdf “Myanmar Economic Monitor Jan 2022” – World Bank Group.

[10] https://reliefweb.int/disaster/fl-2021-000095-mmr

[12] https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/mmr_humanitarian_needs_overview_2022.pdf

[13] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/09/mehl-military-links-to-global-businesses/?utm_source=TWITTER-IS&utm_medium=social&utm_content=3688619862&utm_campaign=Other&utm_term=News-No

[14] https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/FFM-Myanmar/EconomicInterestsMyanmarMilitary/Infographic1_Governance_Structure_of_MEHL_and_MEC.pdf

[15] https://thediplomat.com/2021/03/us-government-to-sanction-military-linked-myanmar-conglomerates-report/

[16] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/6/29/global-witness-report-jade-in-myanmar

[17] https://specialadvisorycouncil.org/cut-the-cash/

[18] https://specialadvisorycouncil.org/cut-the-cash/

[19] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/MyanmarFFM/Pages/EconomicInterestsMyanmarMilitary.aspx

[20] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24868&LangID=E

[21] https://undocs.org/A/HRC/40/68

[22] https://undocs.org/A/HRC/40/68

[23] https://undocs.org/A/HRC/40/68

[24] https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/stories/how-business-finances-the-crimes-of-the-myanmar-military

[25] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/09/mehl-military-links-to-global-businesses/

[26] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/09/mehl-military-links-to-global-businesses/

[27] https://www.irrawaddy.com/opinion/guest-column/what-has-happened-to-myanmars-tatmadaw.html

[28] https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/report/the-economic-interests-of-the-myanmar-military/A_HRC_42_CRP_3.pdf “The economic interests of the Myanmar military. Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar” Human Rights Council – Forty-second session 9 – 27 September 2019

[29] https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa16/2969/2020/en/

[30] https://www.asianews.it/news-en/About-5-billion-dollars-from-Total-and-Chevron-flow-into-junta%E2%80%99s-secret-accounts,-NGO-says-16290.html

[31] https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0024

[32] https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/ForeignAffairsAR19-20/Interim_Report

[33] https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_new-zealand-imposes-sanctions-myanmars-military-after-coup/6201898.html

[34] https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2021/03/5b9cd16b5772-japan-suspends-new-aid-to-myanmar-over-military-coup.html

[35] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/3/britain-announces-new-myanmar

[36] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-myanmar-idUSKBN2B40M8

[37] https://www.reuters.com/world/eu-mulls-arms-embargo-more-sanctions-myanmar-after-appalling-violence-2021-12-30/

[38] https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/sanctions/myanmar.aspx?lang=eng

[39] https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/switzerland-applies-fresh-sanctions-on-myanmar/46750962

[40] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/nug-urges-boycott-of-myanmar-coup-leader-family-businesses.html

[41] https://www.mmtimes.com/news/myanmar-calls-boycott-tatmadaw-linked-products-and-services.html

[42] https://nobusinesswithgenocide.org/campaign-for-a-new-myanmar/

[43] https://actionnetwork.org/letters/tell-your-us-senators-support-the-myanmar-civil-disobedience-movement?source=direct_link

[44] https://m.facebook.com/rejectmmcoup/

[45] https://www.reddit.com/r/myanmar/comments/liszzx/whathappeninginmyanmar/

[46] https://www.facebook.com/hashtag/savemyanmarfrommilitarycoup?source=feed_text&epa=HASHTAG

[47] https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Myanmar-Crisis/Myanmar-civil-servants-boycott-to-pressure-military-after-coup

[48] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmars-veteran-student-leaders-demand-boycott-myanmar-military-businesses.html

[49] https://www.just-style.com/news/unions-urge-boycott-of-myanmar-made-goods/

[50] https://burmacampaign.org.uk/burma_briefing/the-boycott-list/

[51] https://burmacampaign.org.uk/growing-military-company-boycott-campaign-in-burma-needs-international-support/

[52] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/jun/15/japanese-brewery-admits-donating-to-myanmar-army-during-rohingya-crisis-kirin-ethnic-cleansing-rakhine-state

[53] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/12/06/business/corporate-business/kirin-myanmar-military-venture/

[54] https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Myanmar-Crisis/Myanmar-court-rejects-dissolution-of-Kirin-brewery-joint-venture

[55] https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/new-evidence-of-plummeting-sales-means-myanmar-beer-boycott-is-working-activists-say

[56] https://eiti.org/files/documents/meiti_reconciliation_report_2017-2018_final_signed_31st_march_2020.pdf

[58] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-military-owned-brewers-sales-halved-as-boycott-bites.html

[59] https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/how-much-money-does-myanmars-military-junta-earn-from-oil-and-gas

[60] https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/040521-petronas-declares-force-majeure-at-yetagun-offshore-gas-field-in-myanmar

[61] https://www.pwyp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Financing-the-Military-in-Myanmar.pdf

[62] https://eiti.org/files/documents/meiti_reconciliation_report_2017-2018_final_signed_31st_march_2020.pdf

[63] https://earthrights.org/Myanmar/

[64] https://www.asianews.it/news-en/About-5-billion-dollars-from-Total-and-Chevron-flow-into-junta%E2%80%99s-secret-accounts,-NGO-says-16290.html

[65] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/21/chevron-and-total-withdraw-from-myanmar-gas-project

[66] https://www.cityam.com/saturday-read-investors-are-fleeing-myanmar-as-coup-grows-more-deadly/

[67] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-01-27/woodside-out-of-myanmar-ahead-of-february-1-coup-anniversary/100785758

[68] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-01-27/woodside-out-of-myanmar-ahead-of-february-1-coup-anniversary/100785758

[69] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/27/woodside-petroleum-to-pull-out-of-myanmar-one-year-on-from-military-coup

[70] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/27/woodside-petroleum-to-pull-out-of-myanmar-one-year-on-from-military-coup

[71] https://www.marketscreener.com/quote/stock/PTT-EXPLORATION-AND-PRODU-6491595/news/Oil-majors-TotalEnergies-and-Chevron-withdraw-from-Myanmar-37605611/

[72] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmars-kbz-group-dissolves-subsidiary-that-operated-jade-mine-with-military.html

[73] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/MyanmarFFM/Pages/EconomicInterestsMyanmarMilitary.aspx

[74] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmars-kbz-group-dissolves-subsidiary-that-operated-jade-mine-with-military.html

[75] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/german-food-giant-metro-ends-operations-in-myanmar.html

[76] https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/british-american-tobacco-pulls-out-army-ruled-myanmar-2021-10-12/

[77] https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/telenor-sells-myanmar-operations-m1-group-105-mln-2021-07-08/

[78] https://www.bbc.com/news/business-57066915#:~:text=In%20a%20statement%20sent%20to,and%20was%20reviewing%20its%20tenancy.

[79] https://www.reuters.com/article/myanmar-politics-edf-idUSL1N2LH1T5

[80] https://www.info-birmanie.org/info-birmanie-justice-for-myanmar-reporters-sans-frontieres-et-sherpa-saluent-le-retrait-de-voltalia-apres-un-an-de-discussions/

[81] https://www.wsj.com/articles/for-foreign-businesses-in-myanmar-coup-creates-unworkable-situation-11616324404

[82] https://www.gtreview.com/news/asia/foreign-businesses-exit-myanmar-over-coup/

[83] https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/12/8/meta-to-ban-myanmar-military-owned-firms-from-its-platforms

[84] https://www.cityam.com/saturday-read-investors-are-fleeing-myanmar-as-coup-grows-more-deadly/

[85] https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/joint-venture-partner-urges-court-to-take-action-in-case-against-mehl ; https://newsviews.thuraswiss.com/singapore-firm-taking-myanmar-military-conglomerate-to-court/

[86] https://www.ajudaily.com/view/20181106160627978

[87] https://www.globaldata.com/company-profile/posco/

[88] https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/shwe-gas-project/

[89] https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/posco-continues-development-of-shwe-gas-project

[90] https://newsroom.posco.com/en/yangon-myanmar-gets-new-landmark/

[91] https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/press-releases/joint-press-release-response-to-posco-from-justice-for-myanmar-and-korean-civil-society-in-support-of-democracy-in-myanmar

[92] https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/posco-international-reviewing-dividend-payments-myanmar-gas-project-2021-05-28/

[93] https://www.econotimes.com/POSCO-to-Terminate-Business-Tie-Up-with-Firm-Backed-by-Myanmar-Military-1606760

[94] https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/posco-continues-development-of-shwe-gas-project

[95] https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/enough-is-enough-activists-file-complaints-against-south-korean-companies-funding-myanmar

[96] https://ilmanifesto.it/armi-al-myanmar-litalia-fa-triangolo/

[97] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/new-crony-brokers-israeli-aircraft-parts-for-myanmar-air-force.html

[98] https://icsin.org/blogs/2021/09/08/seven-months-post-coup-decoding-chinas-myanmar-policy/

[99] https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/understanding-the-relations-between-myanmar-and-china/

[100] https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/understanding-the-relations-between-myanmar-and-china/

[101] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/supplying-02182021091648.html

[102] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-china-sign-dozens-deals-bri-projects-cooperation-xis-visit.html

[103] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/supplying-02182021091648.html

[104] https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/myanmar-cso-report-reveals-chinese-state-owned-mining-companies-partnership-with-myanmar-economic-holding-limited-mehl/

[105] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/supplying-02182021091648.html

[106] https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2018-09/ssg-report-chinas-role-in-myanmars-internal-conflicts.pdf “China’s Role in Myanmar’s Internal Conflicts” – United State Insitute of Peace – 2018 – page 12

[107] https://www.navyrecognition.com/index.php/naval-news/naval-news-archive/2021/december/11171-myanmar-commissions-the-ums-minye-kyaw-htin-chinese-made-type-035-submarine.html

[108] https://www.limesonline.com/cina-myanmar-birmania-sottomarino-vie-della-seta-bri/126390

[109] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/supplying-02182021091648.html ; https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/growing-chinese-investments-in-myanmar-post-coup/ ; https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/myanmar-cso-report-reveals-how-myanmar-economic-holding-limited-mehl-profits-from-partnership-with-chinese-state-owned-mining-companies-companies-did-not-respond/ ; https://www.gnlm.com.mm/sezs-are-important-to-seek-employment-opportunities-and-techniques-and-secure-economic-development-of-the-country-similar-to-that-of-neighbouring-and-other-countries-vice-senior-general/?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=pmd_kD9Wpi8rIoBaDld0eDa9Sob9ehBkjpAQf_7_XGTy8Bc-1630224284-0-gqNtZGzNAtCjcnBszQXl

[110] https://www.amistades.info/post/il-myanmar-dei-militari-visto-dalla-cina-un-pericolo-o-un-alleato

[111] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/30/myanmars-military-turns-to-buddhism-in-bid-for-legitimacy ; https://www.irrawaddy.com/specials/myanmar-and-russias-close-post-coup-relationship.html

[112] https://sicurezzainternazionale.luiss.it/2021/06/19/myanmar-assemblea-generale-onu-approva-embargo-sulle-armi/

[113] https://sicurezzainternazionale.luiss.it/2021/06/23/myanmar-lesercito-si-fortifica-grazie-alla-fornitura-armi-russe/

[114] https://www.interfax.ru/world/773409

[115] https://sicurezzainternazionale.luiss.it/2021/06/23/myanmar-lesercito-si-fortifica-grazie-alla-fornitura-armi-russe/

[116] https://www.irrawaddy.com/specials/myanmar-and-russias-close-post-coup-relationship.html

[117] https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Myanmar-Crisis/Japan-slow-to-join-global-chorus-denouncing-Myanmar-coup

[118] https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/12/02/japan-plays-diplomatic-double-game-rights-myanmar

[119] https://www.jica.go.jp/myanmar/english/office/topics/press201104.html ; https://www.jica.go.jp/myanmar/english/index.html

[120] https://www.twai.it/journal/tnote-97/

[121] https://www.jobnet.com.mm/companies/j-sat-recruitment-agency-for-japanese-company/e-1408

[122] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2022/01/10/business/myanmar-japan-business-outlook/

[123] https://time.com/battling-for-blood-jade/

[124][124] https://kdng.org/2017/05/15/myanmars-kachin-state-holds-the-richest-jade-mines-in-the-world/

[125] https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/myanmars-largest-jade-mining-town-semi-precious-stone-prized-chinese-costs-more-money

[126] https://www.dailysabah.com/world/asia-pacific/myanmar-junta-has-full-control-of-jade-profits-as-fighting-rages

[127] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/natural-resource-governance/conflict-rubies-how-luxury-jewellers-risk-funding-military-abuses-myanmar/

[128] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/jade-07012021152039.html

[129] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/jade-07012021152039.html

[130] https://crisis24.garda.com/alerts/2022/02/myanmar-additional-fighting-between-military-and-armed-groups-likely-in-kachin-state-following-clashes-in-early-february

[131] https://time.com/battling-for-blood-jade/

[132] https://time.com/battling-for-blood-jade/

[133] https://hindustannewshub.com/world-news/myanmar-landslide-over-70-people-missing-in-a-landslide-in-a-mine-in-myanmar/

[134] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/natural-resource-governance/conflict-rubies-how-luxury-jewellers-risk-funding-military-abuses-myanmar/

[135] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/natural-resource-governance/conflict-rubies-how-luxury-jewellers-risk-funding-military-abuses-myanmar/

[136] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/natural-resource-governance/conflict-rubies-how-luxury-jewellers-risk-funding-military-abuses-myanmar/

[137] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/natural-resource-governance/conflict-rubies-how-luxury-jewellers-risk-funding-military-abuses-myanmar/

[138] https://www.voanews.com/a/relief-group-says-2-members-killed-in-myanmar-violence-/6372917.html

[139] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/whos-myanmars-national-unity-government.html

[140] https://www.dw.com/en/myanmar-junta-designates-shadow-government-as-terrorist-group/a-57473057

[141] https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/nug-stepping-up-efforts-to-supply-guerrilla-fighters-with-weapons-says-defence-official

[142] https://www.diis.dk/en/research/defecting-soldiers-are-a-significant-symbolic-blow-to-myanmars-military-rule

[143] https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/nug-stepping-up-efforts-to-supply-guerrilla-fighters-with-weapons-says-defence-official

[144] https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/myanmar-un-anno-dopo-cala-il-buio-sale-la-tensione-33045

[145] https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/ive-never-seen-such-solidarity-we-expect-the-revolution-to-succeed-this-year-nug-prime-minister

[146] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-junta-arming-training-civilians-as-losses-defections-mount.html

[147] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/4/myanmars-aung-san-suu-kyi-faces-eleventh-corruption-charge ; https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/8/fleeing-violence-in-myanmar-thousands-camp-along-thai-border-river

[148] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/4/myanmars-aung-san-suu-kyi-faces-eleventh-corruption-charge

[149] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/10/aung-san-suu-kyi-found-guilty-over-walkie-talkie-charges-reports

[150] https://www.voanews.com/a/new-corruption-charges-against-myanmar-s-aung-san-suu-kyi/6398145.html

[151] https://www.voanews.com/a/new-corruption-charges-against-myanmar-s-aung-san-suu-kyi/6398145.html

[152] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2022/02/01/asia-pacific/politics-diplomacy-asia-pacific/year-after-myanmar-coup-sanctions/

Leave a Reply