BEYOND CONCRETE: HUMANITY FLEEING THE CITIES

Man has always been on the move, searching for a better place to live. For most of human history, most people throughout the world have lived in small communities. The process of industrialisation has led to the formation of ever larger metropolises, which have become centres of economic and social life, attracting large human flows and thus triggering a process of extreme urbanisation and a consequent abandonment of the countryside.

Something has changed: in today’s world, made up of people for whom living in cities seemed the epitome of dreams and possibilities, we are witnessing a mysterious phenomenon: the massive depopulation of cities – especially in the economically richer areas of the planet. The transformation of society from industrial to post-industrial, including the shift from a manufacturing economy to a knowledge economy, brings with it profound changes in the choices and aspirations of the Earth’s inhabitants: the glittering skyscrapers, crowded streets and endless opportunities become part of a past to be distanced from, as more and more people decide to leave the concrete jungle in search of something new. Not least because socialisation, especially after the pandemic in the younger generations, no longer takes place co-presently, but increasingly virtually.

Ghost towns in the United States

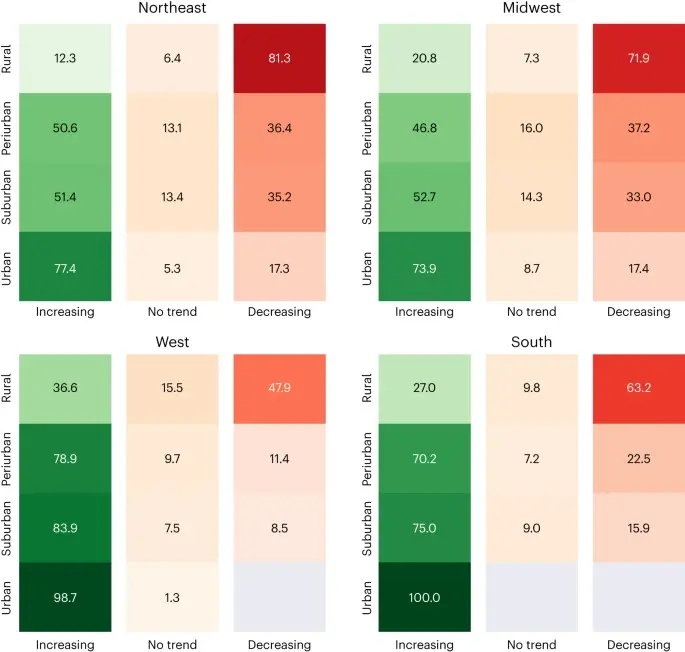

According to the study, cities with lower average household incomes in the Northeast and Midwest are likely to experience greater depopulation over time than those in the West and South[1]

According to a study by the University of Illinois, based on demographic data, a process of depopulation is underway in almost half of US cities. The term ‘depopulation’ commonly refers to a steady decline in the population of cities, which can be caused by a number of factors. This analysis focuses on urban desurbanisation – the outflow of human capital from large cities – which is expected to reduce the population of 15,000 US urban centres (between 12 and 23 per cent) by 2100. The researchers predict that the situation will vary from region to region. The results show that 43 per cent of US cities are losing population, while 40 per cent are increasing and the remaining 17 per cent are fluctuating[2] .

These developments have the potential to trigger a number of social, economic and environmental problems. Population outflows result in a ‘shrinking tax base’ that directly affects basic urban services and has a direct impact on the remaining population of cities, with possible disruptions to the city’s life support system (electricity, transport, water, waste disposal, communications) and the creation of ghost towns[3] .

The authors of the study hope that their work will shift the focus of policymakers towards flexible, modular and multifunctional urban planning for specific places and cities, instead of planning based only on economic growth. In the case of the United States, more flexibility in administrative and financial decision-making will be needed to adapt to democratic changes and avoid dramatic scenarios.

There is no doubt that adapting to dramatic demographic change requires a profound cultural shift in the planning and engineering community away from the traditional planning based on the (increasingly untrue) equation that bigger cities offer more and better working conditions. The development of the smart working concept is also changing the way a company is run, allowing large companies to imagine a near-term future without immense and expensive offices[4] .

What is killing the cities?

In the dreams of ever wider layers of the population, a return to the countryside is increasingly important[5]

Urban depopulation can be caused by a number of reasons and is often a complex and interconnected set of factors. Economic factors, such as the availability of jobs, are extremely influential. A decline in the economic potential of companies, a decrease in investment, crises or a shift to more efficient technologies that reduce human involvement in technological processes can lead to the loss of jobs and, consequently, to population decline.

Demographic changes directly influence the number of residents in cities. If the urban population ages, this can lead to a decrease in birth rates and an increase in the proportion of elderly people. As a result, the flow of young families decreases and the proportion of people of retirement age increases, reducing the overall population level of the city[6] . The migration of young people in search of better living spaces is also becoming more and more substantial.

The departure of qualified young people from small and medium-sized cities to prosperous megacities in search of educational and professional opportunities is not compensated either quantitatively or in terms of educational level by the migration of the rural population. This outflow of ‘young brains’ generates negative migration balances and serious decapitalisation processes in education[7] .

The change in family patterns, the dramatic increase in the percentage of single-parent households, convinces people that it is better to live in smaller cities or rural areas: due to lower housing costs, access to nature and a quieter environment, this can lead to a decline in human employment potential in large cities. Social and cultural factors, as well as government migration policies, may encourage people to migrate to other regions where living conditions are more attractive, safer or bureaucratically simpler.

The state of the cities’ infrastructure, including transport possibilities, the availability, accessibility and quality of important facilities for living, such as schools or medical centres, the environmental conditions of the cities, crime rates: all these ‘little things’ can both attract flows of people out of the cities and create differences in the population structure and lead to a reduction in the total number of residents[8] .

Cyclicality of processes

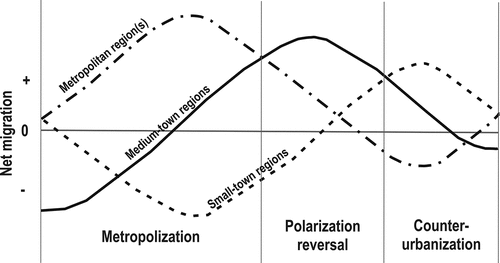

Graphical representation of Differential Urbanisation Theory[9]

Like almost everything in our lives, the urban development cycle now has a scientific basis. According to the 2005 ‘Differential Urbanisation Theory’[10] , the urbanisation process consists of six stages, divided into three cycles: urbanisation, reversal (in scientific language – reversion of polarisation) and desurbanisation.

The initial phase of urbanisation is characterised by the rapid growth of large cities at the expense of small and medium-sized ones. In the second third of this period, the growth of large cities and the population loss of small cities reaches its apogee. The beginning of the reversal marks the leadership of the medium-sized centres; the major cities lose ground and lose attractiveness, while the small cities increase their attractiveness. In the next phase of the reversal, small cities rush forward, even though medium-sized cities are still ahead, and the growth index of major cities becomes negative. Counter-urbanisation (desurbanisation) opens the initial phase of small settlements, where immigrants rush in; medium-sized centres lose population; large centres, past their lowest point, stabilise.

Then everything returns to the initial order and the process repeats, but with a decrease in the amplitude of the curves on both axes: the stages themselves shorten and the gaps in the settlement class indicators narrow. The general mobility of the population, the frequent changes in migration cycles (from large centres and vice versa) combine with the stability of the established settlement hierarchy[11] .

Technological progress brings people ‘back to earth’

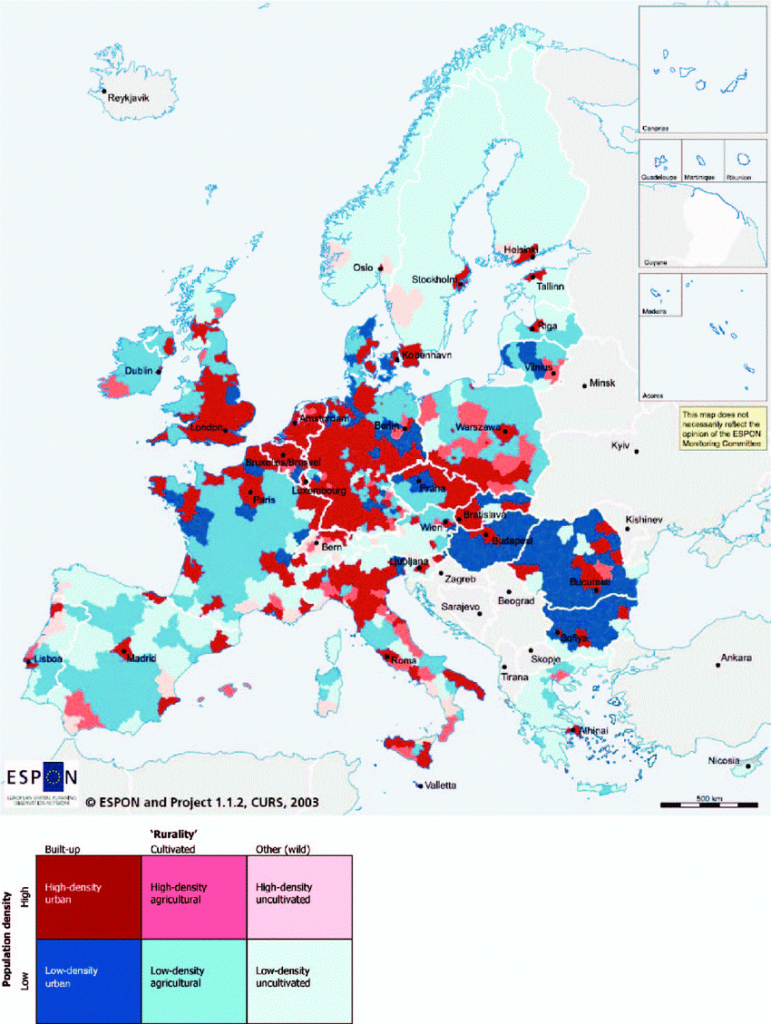

The map of depopulation of big cities in the European Union[12]

The Industrial Revolution encouraged mankind to move to cities, leading to a boom in urbanisation. Job opportunities, higher and more comfortable living standards, access to education and healthcare, and centralised services to make life easier led to the rapid development of megacities around the world. But unstoppable technological progress has brought structural changes.

The rapid development of information technology shows that one does not necessarily have to live where one works. Today, there is a global playing field where a company’s headquarters can easily interact with employees around the world through digital technology. Cloud services, online conferencing, collaboration and learning platforms – all these tools enable productive workflows even when employees are not in the same office, as long as the Internet is available.

This is a great way for companies to save money. The technical workplace equipment of an employee living in a remote area is a much cheaper solution than renting an office in a big city. In addition, attracting human capital for remote work from areas far away from the city can save on wages, because the payment of labour is also zonal in nature.

The hectic pace of life, cosmic housing prices, constant stress, difficulties in commuting and time lost in traffic jams are increasingly driving people to live outside the city. And while the city once offered more opportunities for consumption and education, today everything can be bought online with home delivery and any skills and knowledge can be learnt through online educational platforms and initiatives without having to visit cities. Improved infrastructure in rural areas makes life more convenient, with a much lower cost of living. And increasingly, the clean air, tranquillity, open spaces and proximity to nature outweigh the allure of city lights[13] .

In 2018, the United Nations predicted that two-thirds of the world’s population would live in cities by 2050, but in 2019 a virus disrupted the pattern of urban growth. The COVID-19 pandemic has fostered the trend of de-urbanisation. Everything that was once attractive about living in a big city has become inaccessible, and densely populated urban areas have turned into dangerous hotbeds of disease, with many people trapped in their homes, without a social life, but with the need to continue working from a home office, raising children remotely, and running a household.

This isolation has a strong psychological impact and has driven many residents to ‘flee’ the concrete jungle. In addition, massive job cuts have caused an exodus of residents who are no longer able to pay for their lives in the city[14] . But quarantine has shown that the economic mechanism can continue to work, even if a significant part of the workforce will work remotely from home or in offices outside the megacities and financial centres of the world, migration to the city is no longer a requirement for employment. The entire social system requires transformation and special attention[15] .

Large cities and mega-cities still play a leading role in the distribution of human flows, but it is clear that they require a rethink with a strong emphasis on sustainability and a case-by-case approach. The pandemic has triggered lifestyles and working patterns almost all over the world and it is difficult to predict how much this will affect the balance between urbanisation and de-urbanisation in the coming years[16] .

Smart cities

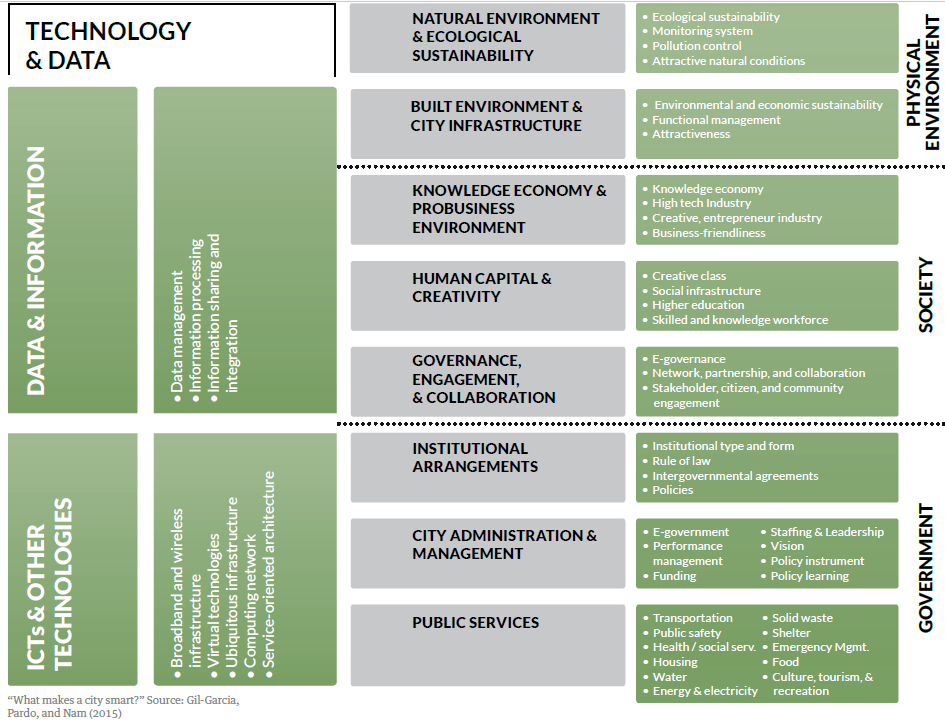

What makes a city ‘smart[17]

In today’s world, especially in developed countries, ‘shrinking cities’ have given rise to the need to make cities smarter in response to change. “The ‘smart city’, or Smart City, is an interconnected system of information and communication technologies with IoT, i.e. the Internet of Things, that simplifies the management of internal urban processes and makes residents’ lives more comfortable and safer[18] .

While growing cities struggle to modernise and expand their infrastructure, shrinking ones must focus on sustainable financial models for the management and maintenance of existing infrastructure to avoid its complete decline, which can have a very negative impact on the remaining urban population. For example, on average, a blighted property can cost a city government tens of thousands of dollars per year in direct and indirect costs, such as property and facility maintenance, depreciation of adjacent properties, uncollected taxes, and more.

Initially, the smart city concept was based on technical aspects such as smart and efficient buildings, energy and communication. The smartest cities were those that used these technologies to save money and create better infrastructure. However, residents were excluded from this analysis, because a smart city strategy is a more socio-technical concept that should mainly focus on the benefits of citizens.

The aim is to make cities not only more compact, but also to support people staying in urban areas by making healthcare and transport ‘smart’, to provide sustainable economic and employment opportunities for citizens, to involve citizens in urban life and decision-making together with local authorities, to create a favourable ecological environment by controlling air and water quality, regulating traffic, recycling waste, etc.

Moreover, every city is unique: what worked in one case may be ineffective in another. Therefore, this method of improving well-being requires a careful analysis of the city’s needs and problems and the specific innovations proposed as solutions to these problems, excluding the possibility of investing ‘blindly’ in ‘something fashionable’ that has worked for others. After all, it is only possible to save the city from ‘extinction’ by introducing social, institutional, organisational and only then technical innovations[19] . But are politicians ready for this?

The world is changing and the settlements we have created are responding accordingly. Displacement, migration and the search for a better place have always been the norm for our society, as have changes in our habitats. That is, until it became a loss for nations. In creating huge, monumental mega-cities, human thinking is geared towards short-term benefits and, when faced with the real threat of extinction, will have to address the unique needs and possibilities of its creations.

USA030

[1] https://nypost.com/2024/01/18/news/thousands-of-us-cities-are-predicted-to-become-ghost-towns-by-2100-new-study/

[2] https://hi-news.ru/research-development/cherez-100-let-v-ssha-poyavyatsya-tysyachi-gorodov-prizrakov.html

[3] https://www.nature.com/articles/s44284-023-00011-7#Sec10

[4] https://www.planetizen.com/news/2024/01/127045-depopulation-projected-thousands-us-cities

[5] https://futuristspeaker.com/future-trends/deurbanization-how-will-this-new-trend-affect-you-in-the-future/

[6] https://urbact.eu/small-cities-potential-best-place-live-europe

[7] https://population-europe.eu/research/policy-insights/urban-depopulation-and-loss-human-capital-emerging-phenomenon-european

[8] https://www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/events/calendar/conferences/the-causes-and-consequences-of-depopulation

[9] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/figure/10.1080/15387216.2023.2220344?scroll=top&needAccess=true

[10] https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/fr-1.1.2_revised-full_31-03-05.pdf

[11] https://books.econ.msu.ru/Demography/chap15/15.1/15.1.2/

[12] https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-of-the-urban-rural-typology-from-the-ESPON-project-on-Urban-rural-relations-in_fig2_247513429

[13] https://www.onbenchmark.com/blog-detail/beginning-of-deurbanisation

[14] https://eu.usatoday.com/story/money/2020/05/01/coronavirus-americans-flee-cities-suburbs/3045025001/

[15] https://globaljournals.org/GJHSS_Volume21/2-Reverse-Urbanization.pdf

[16] https://www.theearthandi.org/post/de-urbanization-trend

[17] https://dubaipolicyreview.ae/why-smart-cities-fail-how-understanding-context-can-save-your-citys-future/

[18] https://center2m.ru/smart-city-about

[19] https://dubaipolicyreview.ae/why-smart-cities-fail-how-understanding-context-can-save-your-citys-future/

Leave a Reply