RWANDA, CONGO AND UGANDA: THE CURSED BORDER

While the eyes of the world are on the Russian-Ukrainian border and that between China and Taiwan, conflicts of planetary importance are being fought as if it were pointless to worry about tomorrow. There is a geographical axis, running from Ethiopia and Eritrea to Cabinda, the Angolan enclave in the Congo DRC, on whose routes two thirds of the world’s strategic minerals pass – and go to China, or Russia, or the West, or the Arab countries, or India. On the ground they fight with acrimony and cynicism, in an undeclared war that costs thousands of lives every year.

This war is played out on three tables: the first, that of logistics, is the one at which the most dangerous players are the Angolan government[1], the Chinese government[2], the French Bolloré group, and the commodities multinationals[3]. The second table is that of the explosion of the oil market – at a time when, in planetary conferences, the world is claiming that it wants to end the petrol era and switch to renewable energy[4]. The third is the military one, which is played out on a very long and cursed border, which runs between Congo DRC, Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi and Malawi. The sum of the bets on the three tables should express a winner, but exactly the opposite happens: the confusion increases, and with it instability, economic crisis, and the number of deaths.

Despite negotiations and treaties, people are shot, smuggled, tortured and exploited on that border. North Kivu is the centre of trafficking in minerals, weapons, the slave trade, and the government in Kinshasa, weak and 2000 kilometres away, in order to finance the war, corruption and appease the warlords on the border, has decided to allocate 30 new oil exploitation licences – in the most important and irreplaceable protected areas of the entire continent. In a perverse game, every small move on one of the three tables produces an immediate deterioration on all the others and endangers the security of the entire African continent.

A game board called M23

A Congolese army tank on its way to the border with Rwanda[5]

Between 29 and 30 November last year, the armed group M23 massacred 131 civilians in Kishishe and Bambo, two villages in Rutshuru territory, in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo DRC. The denunciation is by the Joint United Nations Human Rights Office (Unjhro) and the United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO): the 131 victims are 102 men, 17 women and 12 children; there are also 60 people abducted, as well as 22 women and five girls raped[6]. According to investigators, this was a reprisal for clashes between the M23 and the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR – FOCA), the armed groups Mai Mai Mazembe and Nyatura Coalition des Mouvements pour le Changement[7].

The massacres in Rutshuru are not isolated incidents, but are the latest in a long series committed in the DRC in almost 30 years: it is estimated that more than 8 million people have died since 1998 (according to an IRC study, between 1998 and 2008 alone, the conflicts left 5.4 million dead on the ground[8]; to these a further 3 million have been added to date[9]) and several million have been displaced[10]. Impressive numbers. Leaving a deep scar are Congo’s two major wars (1996-1997 and 1998-2003) that began in the east of the DRC – a region that, according to the Kivu Security Tracker, in 2019 alone has at least 130 armed groups fighting not only on ethnic grounds, but also for control of the rich mineral deposits along the border[11]: most number fewer than 200 fighters, but for years they have dominated the war scene, especially in North and South Kivu, making the eastern part of DRC virtually uninhabitable and uncontrollable.

There is a vast illegal trade that arms and finances them, as the DRC possesses enormous mineral wealth: 41% of the world’s cobalt reserves[12] (at least 200,000 ‘informal’ miners are involved in its extraction[13]), 10% of the world’s gold reserves (43 tonnes produced in 2020, counting only the legal trade[14]), over 50% of coltan reserves (a rare and precious mineral that contains tantalum and niobium[15]), as well as copper and tin, and huge resources of diamonds, uranium, and cassiterite – one of the richest subsoils in the world.

The mines, where exploitation and corruption are rampant due to the complicity of politicians[16], are illegally managed by armed groups, but also by the regular army[17]. In South Kivu, more than 60% of the mines are in rebel hands[18], and men, women and children work there indiscriminately (in Katanga alone, in the southern part of Congo, it is estimated that there are between 70,000 and 150,000 artisanal miners, of which about 40,000 are children under the age of 16[19]) who, after 14 hours of work, scrape together a dollar – or die, since during the rainy season it can happen that up to 30 or 40 are buried under landslides or in tunnels in a single day in a single mine[20].

Rwanda is the fuse

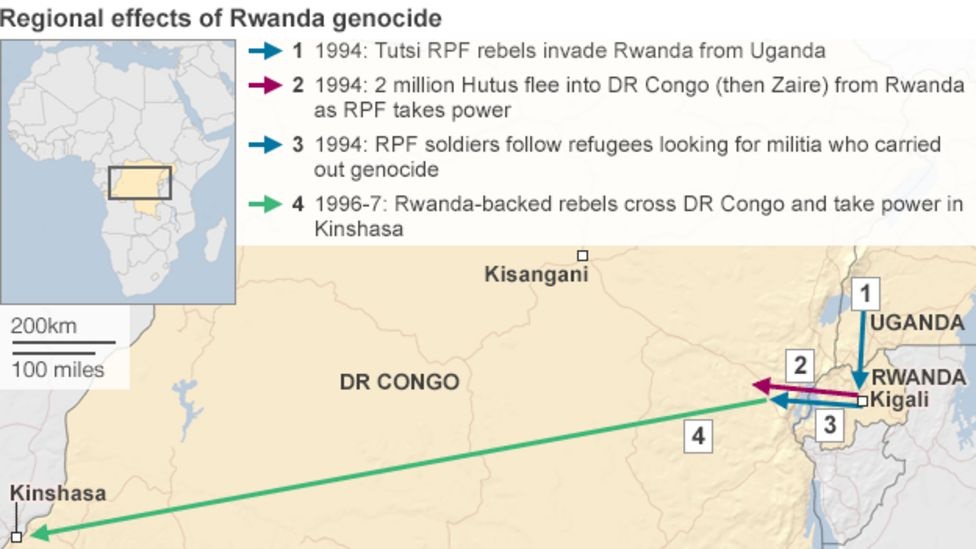

The genocide in Rwanda, origin of the bloody conflicts with the neighbouring Kivu regions[21]

The first event in a long series that turned a relatively peaceful society like the Democratic Republic of Congo into an arena of war was the genocide of the Hutu, at the hands of the Tutsi, in Rwanda in 1994: this tragedy generated an escalation of conflicts unique in modern African history. One of the most significant results is the massive migration of over two million Hutus into the Congolese region of Kivu, who are allowed to take up arms and settle along the border[22] while, along the border with Rwanda, UNHCR camps are set up, in which the armed fronts of the Rwandan ethnic war are replicated, including the Interhamwe and the Army for the Liberation of Rwanda (ALiR)[23].

The vast immigration upsets the balance in Kivu: the Hutus become a dominant force, isolating and attacking the Congolese Tutsis, supported by the Congo army (then led by the kleptocrat Mobutu) and some Kivu politicians[24]. The tensions spread from the south to the north of Kivu, along the Rwandan refugee camps: it was the beginning of a rapid and unstoppable succession of inhuman massacres[25]. In 1996, Rwanda and its Ugandan allies invaded eastern Congo to hunt down the perpetrators of the genocide, triggering what has been called the ‘World War of Africa’[26]. Supported by the Congolese opposition leader Laurent Désiré Kabila, they deposed the bloodthirsty dictator Mobutu, bringing Kabila and his Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo-Zaïre (AFDL) to power[27].

A second, much bloodier war (1998-2003) was on the horizon, triggered by two events: the dismissal of the Congolese Defence Minister James Kabarebe, a Rwandan responsible for the conduct of the first Congo war[28], and Congo’s support for the ALiR, responsible for the 1994 Tutsi genocide. Both Rwanda and Uganda, accusing Kabila of allowing rebel groups to attack their countries from bases in the eastern DRC, attempt to remove him from power by setting up the Rassemblement Conglais Democratie (RCD), a militia composed mainly of Congolese Tutsis[29].

The rebellion turns into a large-scale war involving the armed forces of six countries, including Angola, Zimbabwe and Namibia, which intervene in support of Kabila: the background is the control of the rich diamond, gold and coltan deposits of eastern Congo. The war lasts five years and, besides causing millions of deaths, drags the region into hunger and disease. It is a veritable massacre, halted by the Sun City Agreement of April 2002[30], the subsequent Pretoria Agreement of July 2002[31], perfected by the Luanda Agreement between Uganda and Congo[32], understandings that officially put an end to the war; the transitional government of the Democratic Republic of Congo comes to power in July 2003 – until, in 2006, Joseph Kabila, son of Laurent Kabila, wins the presidency in the DRC’s first democratic elections[33].

In 2004, a new serious crisis broke out between the government and the pro-Rwandan Tutsi rebels of the Congrès National pour la Défense du Peuple (CNDP, created by General Laurent Nkunda[34]), which was quelled by a peace treaty in January 2008, which did not last long: at the end of October, the conflict in the Kivu resumed in all its intensity, with the entry into the war of the Front Démocratique de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR), the UN mission (MONUC), the regional Mai-Mai, and the foreign armies of Angola and Zimbabwe[35]. The fight lasted until 2009, when Rwandan troops arrested Nkunda; on 23 March of that year, the CNDP signed a peace treaty with the government with the agreement to integrate its militias into the national army and have the CNDP recognised as a political party[36].

All against all

8 July 2012: General Sultani Makenga (centre), leader of the M23 rebel group[37]

On 28 November 2011, Joseph Kabila won a controversial election in a climate of great tension and violence[38]. The agreement of 23 March 2009 allows the CNDP rebels to occupy high-ranking positions in the army and extort illegal taxes from companies and mines in the region[39]. On 4 April 2012, the leader of the CNDP, Bosco Ntaganda, with troops loyal to him consisting of around 300 soldiers and integrated into the national militia, mutinied, complaining of poor treatment and claiming a breach of the peace treaty – because their autonomy was threatened[40]: this was the birth of the 23 March Movement (M23).

Composed mainly of Tutsis, it opposes the Hutu militia Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR[41]) and the Mai-Mai militia (created and supported by the DRC[42]). Under the leadership of Sultani Makenga[43] and General Bosco ‘The Terminator’ Ntaganda[44], the M23 group demonstrated significant fighting power with the occupation of Goma, the capital of North Kivu province, in November 2012[45].

A UN report states that the M23 rebels operate under the overall command of the Rwandan defence minister and with the support of Uganda, and that the M23 rebellion enjoys funding from traffickers who derive huge profits from smuggling tin, tungsten and tantalum from the eastern DRC mines[46]. The rebel group split into two factions in February 2013, led respectively by Bosco Ntaganda and Sultani Makenga; the first group fled to Rwanda, and the part led by Makenga, remaining isolated, met its end[47]: repression by FARDC commando battalions and a UN brigade led to its total surrender in November 2013[48].

Sultani Makenga, who fled to Uganda, tries with international support to mediate an end to the fighting[49]: quite unexpectedly, Ntaganda voluntarily surrenders himself to officials at the US embassy in Kigali, asking to be tried by the International Criminal Court in Den Haag[50]. This brings against him seven counts of war crimes and three counts of crimes against humanity committed in Ituri, DRC, between 1 September 2002 and the end of September 2003[51]. The horrific brutalities committed by the rebel group (summary executions, killing of civilians, torture, kidnappings, rape, forced conscription even of minors) are supported by numerous reports, first and foremost that of Human Right Watch in 2013, which also reiterates Rwanda’s support, continually denied by Kigali[52].

In the following December, an important peace agreement was signed between the government and M23: the conditions included the dissolution of the armed group and the end of offensives on both sides and, in exchange, the transformation of M23 into a regular political party and amnesty for the rebels, although the government spokesperson specifies that this is not a general amnesty and that those guilty of war crimes or crimes against humanity will still be prosecuted[53].

The M23 group seems to have been defused, but in 2016 it is back in action, thanks to the serious political instability created by Kabila who, when his term in office ended, refused to resign, triggering violent protests across the country: to quell the uprisings, between October and December, Kabila launches a recruitment drive of at least 200 M23 fighters, taking them from their shelters in the military and refugee camps in Uganda and Rwanda; Kabila provides them with new uniforms and weapons, integrates them into the police corps, the army and the Republican Guard and deploys them in the capital Kinshasa, in Goma and in Lubumbashi[54], where they are guilty of violence, dozens of murders and hundreds of arbitrary arrests[55].

Bosco Ntaganda, M23 leader, surrenders himself to the International Criminal Court in The Hague in March 2013[56]

M23 disappears again. On 30 December 2018, elections are held and Kabila gives way to Felix Tshisekedi, amidst the inevitable accusations of electoral fraud. After six months, a coalition government is formed with the former president, which allows the latter’s men to retain control of key ministries, the legislature, the judiciary and the security services. Bringing security and stability back to the country is certainly one of Tshisekedi’s first programmes, but the division of decision-making and executive bodies between the president’s men and Kabila’s loyalists leads to disappointing results.

The military initiatives and Uganda’s permission to penetrate its territory to hunt down the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF, a violent armed group of Ugandan rebels[57]), the deployment of East African Community (EAC) troops, the court martial instituted in North Kivu and Ituri, or the opening of peace negotiations, accompanied by plans to help the combatants return to civilian life (DDR III Programme[58])[59], are of no use: in the first twenty months of government, according to Kivu Security Tracker, there were 2127 civilians killed and 1450 abducted, an even heavier toll than that of the last 20 months of the predecessor, Joseph Kabila, with 1553 victims[60]. Most of the violence is attributed to the ADF, those whom Tshisekedi promises to ‘exterminate’ during a ‘final offensive’ in October 2019[61].

In a context of widespread violence, in November 2021, the M23 group, under the pretext of the non-implementation of certain clauses of the peace treaty, attacks FARDC positions in Rutshuru, Runyonyi and Chanzu villages, strategic hills between Rwanda and Uganda in the eastern part of the DRC[62]. The use of heavy weapons results in numerous civilian casualties and hundreds of thousands of displaced persons[63]. It is the beginning of a new bloody advance in the north of the city of Goma that does not seem to stop, and once again Rwanda (which denies it) is accused of supporting the rebels with arms and ammunition[64].

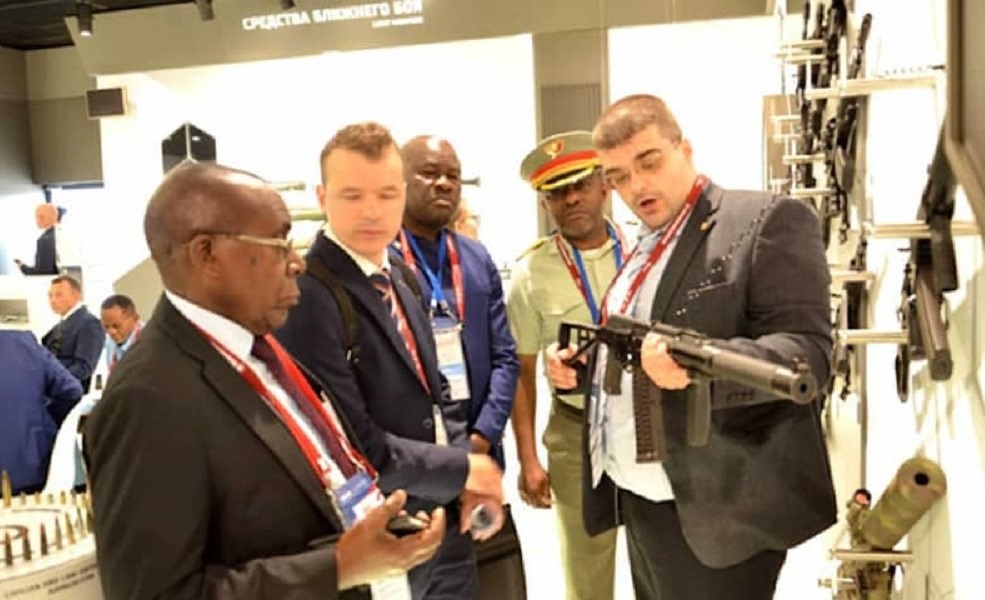

August 2022: DRC Defence Minister Gilbert Kabanda Kurhenga at an arms fair in Moscow[65]

In August 2022, Defence Minister Gilbert Kabanda is in Moscow, and the event does not go unnoticed in the West: concern is high that arrangements will be made for an intervention by Wagner forces. Russian mercenaries, operating in Mali and the Central African Republic, are accused of terrorism and massacres of civilians[66]. Tshisekedi denies this and argues that it is normal to maintain diplomatic relations with Russia, despite the invasion of Ukraine, claiming independence and respect for international treaties. He says he has no need for mercenaries, because the Congolese army is trained to the best of its ability[67].

Rwandan President Kagame insists, he is certain that the DRC is not seeking peace and is hiring mercenaries[68]. According to an investigation by the German newspaper TAZ, the presence in Goma of mercenaries from Romania from the company of Horațiu Potra (the managing director of the Romanian mercenary group Asociatia RALF[69]) is certain: the Mbiza Hotel, in the centre of Goma, is full of white men in uniform who speak French, but have no flags of affiliation; photos of white men carrying AK47s alongside the Congolese army are circulating, but there is no confirmation of their nationality[70].

Given the good relations with Russia and the reassurances made by the Vice-Minister of Defence, Alexander Fomin, who guarantees the Congolese army the necessary weapons, and by Anatoly Punchuk, who reassures Minister Gilbert Kabanda on his country’s willingness to equip the FARDC and train Congolese officers, it seems that the entry of Wagner’s forces into DRC is not at all improbable[71]. The UN also confirms the presence of mercenaries: the Bulgarian company Agemira has a branch in Kinshasa for the maintenance of helicopters and combat aircraft. At the Goma airport, Agemira has around 40 engineers and flight technicians. But it is not only Bulgarians, among them are also Georgians and Belarusians. who are familiar with Russian technology, and Georgians are employed by the DDRC air force as pilots[72].

On 23 November 2022, following a mediation by Angolan President João Lourenço, a ceasefire agreement was reached between Tshisekedi and Rwandan Foreign Minister Vincent Biruta: the agreement envisages an end to M23 attacks from 25 November and its withdrawal from the occupied areas in the following two days; the deployment of the EAC regional force in these areas; and an end to all support for the M23 and other armed groups[73]. Despite the agreement, M23 violence continues. Knowing the truth, in this great confusion, is impossible.

There are two opposing theses. The first is the pro-government one, which sees M23 as a tool in the hands of resource-hungry foreign governments, used to destabilise wealthy areas to plunder; this thesis, however true, ends up ignoring the part of the conflict that is motivated by internal causes. The second, the pro-M23 one, places all the responsibility on the government, which is incapable of administering the area: there is still heavy interference from the Hutus, who pose a serious threat to the Tutsis, and the group aims to be the spokesman of this ethnic group in order to claim the right to security, property and to facilitate the return of Tutsi refugees to their homeland. Both theses are tainted by propaganda. This only turns the area into a minefield.

Raging dogs around the same bone

Mining, where child exploitation is the norm, is dominated by looting[74]

The DRC has 92 million inhabitants and, despite its enormous mineral wealth, continues to be one of the poorest countries in the world: 60 million people live on less than USD 2.15 a day[75]. The situation is linked to the context of instability and insecurity: suffice it to say that in the period 1999-2004, during the second Congolese war, the plundering of the mines caused the DRC to lose more than 10 billion dollars[76]. The drama is ancient, as the DRC has been plundered by foreign governments and companies for more than 500 years – since Portugal first landed on the region’s shores.

From the slave trade in the early 16th century[77] to the exploitation of rubber and ivory in the 19th century by Belgian King Leopold II, who turned the Congo into his personal fiefdom; from the looting of copper during the First World War, to the Second World War when the United States, having defeated Nazi Germany, took control of the world’s most important uranium deposit; during the Cold War, with the US-USSR race for uranium, the US and Belgium conspired to assassinate the hero of independence, Patrice Lumumba, in order to install the dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, who ensured their continued looting of the mineral resources[78].

During the 1980s, at least twenty large international groups from South Africa, France, Canada, the United States and Australia were sharing the resources, vying for control of the main Congolese state mining companies, such as Gécamines (copper and cobalt), Okimo (gold), Miba (diamonds) and Sominki (gold and cassiterite)[79]: Mobutu resists, the state companies are not privatised, and the attempts of the big groups fail, not so much out of a nationalist spirit, but because, for Mobutu, those companies are cows to be milked to enrich himself personally.

With the Rwandan genocide – which coincides with the whirlwind expansion of the electronics market, starved for rare metals, in which DRC is extremely rich – taking advantage of the serious destabilisation in the Kivu region, Rwanda and Uganda take part in the banquet: Rwanda invades the DRC with the help of Ugandan soldiers, the Angolan air force and economic contributions from Zimbabwe and overthrows the dictatorship in Kinshasa, installing Laurent Kabila as president and, from then on, has an easy time running the mines[80].

That the aims were more economic than political are told by the facts: a month before the fall of Mobutu, on 16 April 1997, Kabila’s AFDL entered into a billion-dollar agreement with the American Mineral Fields company for the extraction of copper, cobalt and zinc in the southern province of Katanga: the company acquired 51% of Gécamines[81]. In exchange for an advance, which is used to finance the war, the company also obtains the exclusive right to purchase diamonds from Kisangani[82].

Artisanal miners extracting cobalt from the illegal Shabara mine near Kolwezi[83]

Several other companies are trying to share the spoils: the South African Genscor and Iscor are competing with their Canadian rival Ludin for the copper and cobalt exploitation at Tenke-Fungurume in Katanga; the Canadian Barrick Gold (whose board includes George Bush, the former Prime Minister of Canada Brian Mulroney and the former head of the German central bank Karl Otto Pohl) is vying for the Kilo Moto Gold Office in the eastern province of Ituri: another Canadian company, Banro Resources, has its eye on the Sominki concessions in Kivu[84].

But Kabila is committed to a policy of closure towards the West: on 2 August 1998, with the consent of the international community and the military coordination of the United States, Rwanda and Uganda attempt to overthrow Kabila. The military intervention of Angola, Namibia and Zimbabwe in his support leads to the failure of the attempt[85]. Meanwhile, the looting continued: between September 1998 and August 1999, according to a UN report, ‘the occupied areas of the Democratic Republic of Congo were looted of all their stocks: stocks of minerals, forest and agricultural products, livestock […] Troops from Burundi, Uganda, Rwanda and RCD soldiers from Goma commanded by one officer, visited farms, factories and banks […]. The soldiers were instructed to load products and goods onto their armed vehicles’[86].

Until 2010, in South Kivu, it is largely the Hutu militias of the FDLR that manage the illicit trafficking of important mineral resources such as coltan, uranium and cassiterite; the riches in North Kivu continue to be controlled by former members of the Rwandan armed forces, installed after the Second Congo War, and by Kony’s Ugandan LRA rebels[87]. From 2010 onwards, military operations have redrawn the balance, and the DRC army has regained control: the powerful Lebanese community is also involved in their illegal business, which mainly involves import-export, and the proceeds end up financing Hezbollah[88]. Ituri, the north-eastern region rich in gold, diamonds, coffee and oil, is mostly in the hands of the Congo Liberation Movement (MLC), which has its stronghold here, backed by Uganda; Angola and Zimbabwe, on the other hand, are present in the very rich Katanga area, where they more or less directly control mines of gold and other rare minerals[89].

Rebel groups, foreign countries, regular army, central government, multinational corporations, international NGOs and aid agencies benefiting from rigged aid programmes[90] and, according to Tom Burgis, author of ‘The Looting Machine: Warlords, Tycoons, Smugglers and the Systematic Theft of Africa’s Wealth’, even the World Bank[91], there is no difference between them, they are all sitting at the same banquet intent on dividing up the loot: theft seems to be the only argument that brings all parties together.

The long hands of the great powers

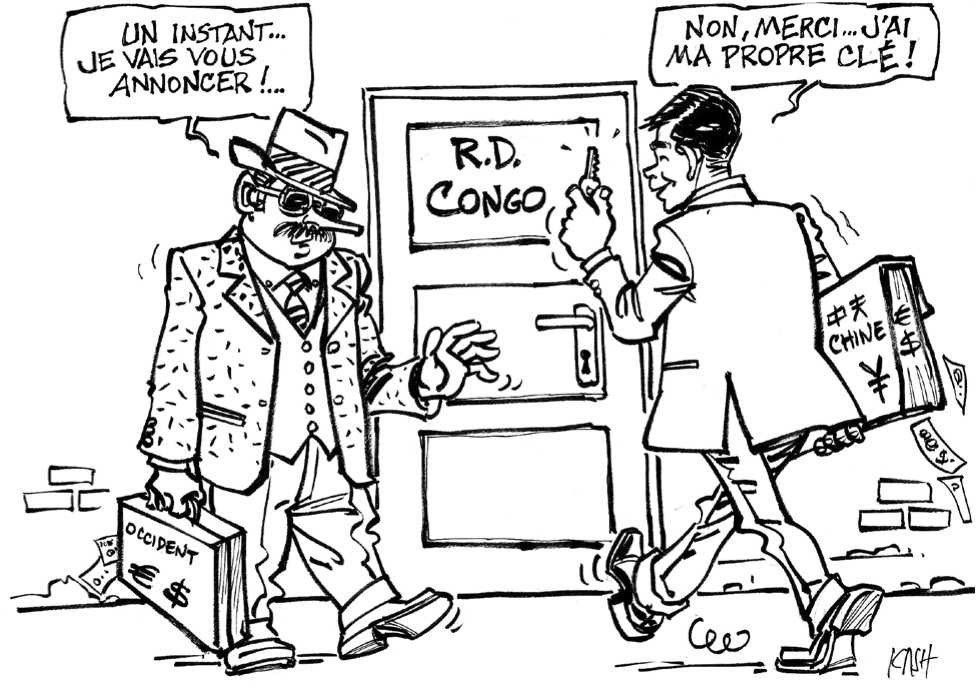

A cartoon ironising China’s privileged relationship with the DRC[92]

China has had an established business relationship with the DRC since the 1970s, but it is in the 21st century that it explodes: in 2000, ZTE is the first Chinese company to invest in telecommunications[93]; in 2006, Huawei signs a contract to supply GSM networks to bring with 500 stations telephone networks and internet connections throughout the country[94] (although, in 2018, Huawei is sentenced to pay $105 million for corruption[95]); for several years, the Chinese government provides military equipment such as vehicles, protective clothing, AK-47 magazines and other material[96], and in 2009 makes a further agreement to provide military aid of $1.5 million[97]; in March 2010, Kabila meets the deputy chief of staff of the Chinese army, a meeting that is described as a ‘new starting point for military cooperation between the two countries’[98].

In 2007, a gigantic agreement (discussed since 2004[99]) between China and the DRC came to fruition. The companies involved are China Railway Group, Sinohydro, China Exim Bank and Gécamines[100]: under the agreement, the Chinese companies undertake to provide funding of USD 9 billion, with a fixed return of 19%[101], for the construction of roads, railways, hospitals, universities, schools and dams, as well as the development of the mining sector; in return, the Congolese government undertakes to supply the companies with ten million tonnes of copper and 600,000 tonnes of cobalt from mines in the south-eastern province of Katanga: a bargain, because the total revenues from the mines could be worth USD 40 to 120 billion – a huge capital gain[102].

The deal faces a number of obstacles: Global Witness immediately denounces the lack of transparency and the risks involved; parliamentary opposition points the finger at what appears to be a ‘sell-out’, as the guarantees are heavily skewed towards investors[103]. Even the IMF (International Monetary Fund, which suspended its programmes in DRC in 2006 due to fiscal mismanagement and corruption in the then transitional administration), expresses strong reservations, believing that the agreement disproportionately increases DRC’s debt[104]. In 2009, the agreement is renegotiated to USD 6 billion, but opposition objections and criticism from Global Witness do not subside – the agreement is secret, and information is leaked about unbalanced guarantees, high risks and no guarantees for workers and the environment[105].

Reports of Chinese companies’ logging and mining activities, which violate the environment and human rights, come to light: an investigation by EL PAÍS/Planeta Futuro[106] denounces the logging and trade of the precious Afrormosia in North Kivu, a protected and endangered tree species, by FODECO[107]; other Chinese companies bribe authorities and the military to illegally extract and export timber and precious minerals; corruption is at an extremely high level, with money everything is bought, licences, contracts, permits, concessions, silence about criminal activities; furthermore, Chinese workers have no medical care or legal working hours, and if they are lucky they earn $3 in a day; one worker interviewed denounces “Half a cup of rice a day, we sleep on the floor, no mosquito nets, no contract, no infirmary… We are like beasts’[108].

And yet, in what seems to be ‘no man’s land’, it happens that complaints of abuse are heard: in August 2021, after months of agitation by the (mostly foreign) workers in the gold mines under Chinese control and angry protests by residents who see their farmland devastated, the governor of South Kivu province decided to halt operations in six mines in order to protect ‘the interests of the local population, the environment and respect for human rights’[109]. a faint light of hope. The complaints are always the same: exploitation, violation of the mining code, environmental devastation, production without tracking[110].

3 March 2020: President Felix Tshisekedi and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in Washington[111]

In December 2021, what the Chinese had promised to be the ‘Deal of the Century’ was engulfed in scandal: Mediapart and the NGO Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa revealed that most of the promised infrastructure was never realised. The money that should have been used to build them, 64 million dollars from the state coffers and those of Gécamines, deposited in an account at the Banque Gabonaise et Française Internationale (a bank in which the Kabila family owns a stake[112]), is paid into secret accounts of Kabila, his relatives and his allies[113]. The Chinese pay the state an equivalent amount, but this disappears into the vortex of public debt and the agreement, even today, has not been fulfilled[114].

In February 2022, POREG (Policy Research Group[115]) makes heavy accusations against the Chinese companies BM Global Business, Congo Blueant Mineral, Oriental Resources Congo, Yellow Water Resources and New Oriental Mineral. According to POREG, these companies collaborate with gold smuggling networks, transporting the precious goods via the Ruzizi River towards Burundi, Lake Kivu towards Rwanda and Lake Tanganyika towards Tanzania; the networks, in turn, support the illegal supply of arms and ammunition in DRC and the Great Lakes region[116]. The Institut Français des Relations Internationales accuses the Congolese armed forces of protecting this illegal trade[117].

It is not only China that comes to DRC – although the latter holds 70% of the mining sector in DRC[118] – but also Europe, South Africa and the USA. The trade relationship between the US and the DRC dates back to 1984, when the Bilateral Investment Treaty was signed[119], and has been growing ever since: US exports of goods to the DRC in 2019 are worth $132 million, up 69.1% ($54 million) from 2018 and 65.9% from 2009, while imports of goods from the DRC (including cocoa, diamonds, spices and wood) are $22 million in 2019, down 56.3% ($28 million) from 2018 and 93.4% from 2009[120].

According to a 2000 law, the African Growth and Opportunity Act, sub-Saharan African countries can export their goods to the US duty-free if they respect certain principles relating to the rule of law, political pluralism, labour rights and market economy. In the case of the DRC, this opportunity was denied by Barack Obama in 2010, but was restored ‘on trust’ in 2019 immediately after Tshisekedi’s election[121].

On 13 December 2022, the United States signed an agreement with the DRC (and Zambia, the world’s sixth largest producer of copper and Africa’s second largest producer of cobalt) to secure the supply of rare metals needed for energy conversion, much of which is controlled by China: the memorandum of understanding speaks only of support for the two countries in the creation of an ‘integrated value chain for the production of batteries for electric vehicles in the DRC and Zambia, ranging from the extraction of raw materials to processing, manufacturing and assembly’[122]. Also in the deal is the allocation of $150 million for the construction of a Mingomba copper-cobalt mine in Zambia by KoBold Metals, a start-up backed by a coalition of billionaires including Bill Gates (with his Breakthrough Energy Ventures) and Jeff Bezos[123].

The imposing Grand Inga dam[124]

The agreements with the US come at the most difficult time between Beijing and Kinshasa: China controls 15 of the 19 cobalt mines (essential for lithium ion batteries), from which it obtains 60% of its needs, but a billion-dollar dispute that began in July 2022 with Gécamines forced the Chinese CMOC to suspend exports and call into question the trade agreements[125]: a heavyweight incident between China and the DRC, which threatens to trigger a domino effect on other contracts already under indictment for unfair practices by both the DRC and the West[126].

But in 2021 it is Australia that wins the investment palm: Fortescue Metals Group (FMG), owned by Australian mining magnate Andrew Forrest, enters into an agreement for the development of the Grand Inga project, the world’s largest hydroelectric plant for the production of hydrogen, an investment worth USD 80 billion; International Rivers[127] expresses deep concern because, according to the environmental group, the agreement is made in the absence of transparency requirements and this could lead to serious violations of environmental obligations[128].

France is present in the DRC with Perenco, a multinational company specialising in the management of depleted oil wells and which has numerous reports of serious environmental and human rights violations in the various countries where the group operates[129]. In November 2022, Sherpa and Friends of the Earth France, supported by the Environmental Investigation Agency, after years of investigation, took legal action against the company: Perenco, which operates in the Parc Marin des Mangroves nature reserve, had for years spilled oil into the environment, dumped oil waste without prior treatment, caused ‘chronic pollution of water, air and soil’, and seriously damaged the health of inhabitants[130].

A forthcoming environmental catastrophe

The peat bog forest of Salonga National Park, threatened by oil, agricultural and industrial exploitation[131]

The Cuvette Basin (Central Basin) is a rainforest region, between Congo and Congo DRC, which includes the Salonga National Park where, in 2014, European scientists discovered the existence of an immense peat bog of inestimable value. The authors of the discovery ventured with great difficulty to inspect this impervious place, far from any human activity and with a very rich biodiversity[132]: it is a vast swamp, covering 145,000 square kilometres (an area the size of the United Kingdom, the largest in the world), entirely covered by a layer of peat that reaches a depth of 5.9 metres[133]. The preciousness of peatlands is that they trap, during the thousands of years of their decomposition cycle, an enormous amount of carbon, becoming a giant reservoir and a natural regulator useful for keeping the planet’s atmosphere in balance: peatlands cover only 3% of the earth’s surface[134] but store a third of the carbon produced[135].

Simon Lewis, the expedition’s director, says: “Its location naturally provides protection. And much of the area in the Republic of Congo is already a community reserve: it is managed by the Wildlife Conservation Society, the government and local people. They have a plan to manage the area and also increase their livelihoods and incomes’[136]. But unfortunately things are different. CoMiCo (Compagnie Minière Congolaise), a company with an opaque off-shore structure, partly owned by Guernsey-registered Central Oil and Gas[137], which in turn holds a 40% stake in CoMiCo, while nothing is known about the remaining 60%.

The company is represented by Montfort Konzi, a former Congolese politician and member of the Movement for the Liberation of Congo, and Idalécio de Castro Rodrigues Oliveira, a Portuguese businessman under investigation for corruption[138] by the Brazilian authorities in connection with ‘Operation Car Wash’[139]. In 2007, it obtained the rights to three oil blocks in the DRC: in particular, the company wants to extract oil within the boundaries of the Salonga National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage area[140]. Despite the constraints, the operation is about to be made possible thanks to the support of Tshisekedi, who is working to reduce the boundaries of the park to allow its exploitation[141]. In 2015, a new, more restrictive oil code arrives, but despite this, CoMiCo’s contract is approved in February 2018, a fact that makes the legitimacy of the agreement doubtful[142].

In October 2017, the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI), of which Norway is the main funder, gives the go-ahead for the transfer of USD 41.2 million to the DRC’s national fund for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation[143]: the condition is that the Congolese government puts in place a ‘solid action plan’ with internal control measures, which is not the case but which does not prevent the transfer of funds.

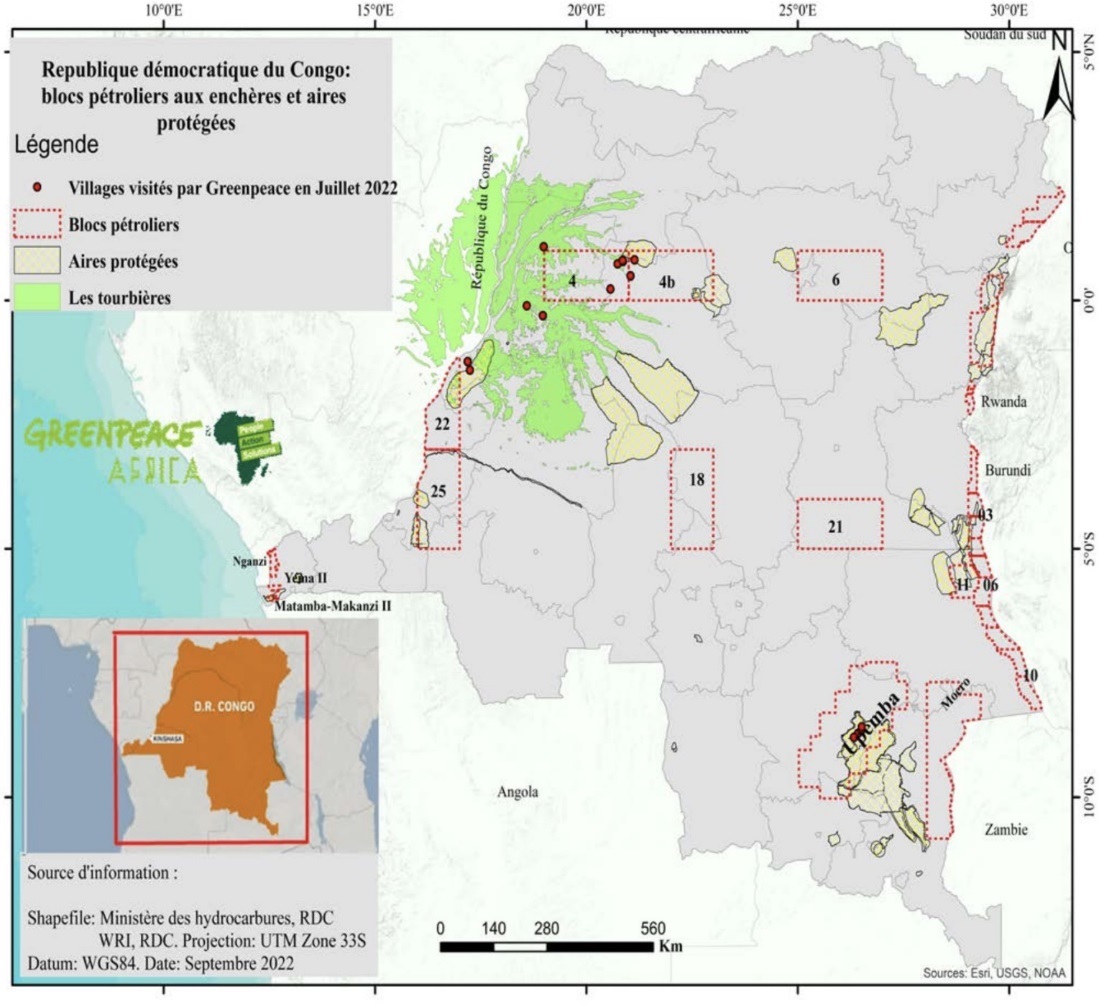

Oil blocks in the Republic of Congo and DRC invade precious peatlands[144]

On 1 February 2018, the Congolese Minister of the Environment, Amy Ambatobe, reinstated 6500 km² of logging concessions cancelled in August 2016[145]: the concessions are awarded to the Chinese-owned forestry companies FODECO (whose licence in the Basoko territory is suspended in November 2019 for serious irregularities[146]) and SOMIFOR – and part of the logging concerns precisely the peat bog area[147]. In March 2018, 14 more concessions are launched to seven different companies[148]: the government’s intent is clear, the country is starving and indiscriminate commercial exploitation is a must.

On 23 March 2018, the Congo and DRC governments signed the ‘Brazzaville Declaration’, announcing their intention to protect the peatlands: the governments pledged to ‘manage’ them in a sustainable manner while avoiding damage to the ecosystem[149]. In fact, however, the agreement does not annul the existing logging concessions, agricultural-industrial exploitation and oil blocks, so that the international community, in May 2018, halts the disbursement of funding[150]. Nevertheless, logging (DRC has one of the highest deforestation rates in the world – it lost 490,000 hectares of rainforest in 2020 alone[151]) and oil exploration continue undisturbed.

On 10 August 2019, the Congolese company Petroleum Exploration and Production Africa (PEPA), a subsidiary of SARPD Oil, announced that it had found hundreds of millions of barrels of oil underground in the Cuvette Central[152]. In Brazzaville, President Denis Sassou-Nguesso (whose nephew runs PEPA[153]) and Environment Minister Arlette Soudan-Nonault go to great lengths to inform that the deposits are not in the peat bog area, but their statements refer to an analysis from 2013, a year before the discovery of the peat bog: according to a report published by researchers at Leeds University, two of the four deposits are in exactly the wrong place[154]. The first is in Ngoki, and is in the hands of the Congolese oil baron Claude Wilfrid ‘Willy’ Etoka: one of the richest men in Africa[155], he is chairman of PEPA and the company’s main shareholder: according to him, oil activities do not harm the environment[156]. Claude Wilfrid ‘Willy’ Etoka is, as it happens, a big political supporter of Sassou-Nguesso[157].

Global Witness, Der Spiegel and Mediapart state that ‘Ngoki’ presents a high risk of corruption and inflicts irreversible environmental damage. Links to Congo’s ruling clan and reckless handling of environmental issues would lead companies to take significant risks by supporting the project’[158]. He continues: “The Congo peatlands are the last place on Earth where fossil fuel extraction should be considered” suggesting oil companies, particularly Total and ENI, but also banks, not to invest in or around the Congo Basin peatlands; the two companies take up the call not to participate in the tender[159]; 15 banks and 7 insurance companies also back out, only ExxonMobil, keeping quiet, hints at its participation[160].

Hydrocarbons Minister Didier Budimbu[161]

According to Global Witness, the amount of oil announced is vastly overestimated[162]: years ago Total and Shell, after exploring the area for oil, concluded that drilling would not be profitable; in January 2016, Shell stated that ‘the combination of high risk and modest size’ led to a decision against investing in the Ngoki block[163].

On 28 July 2022 in Kinshasa, President Felix Tshisekedi presides over the launch of the auction (promoted by Didier Budimbu’s Ministry of Hydrocarbons), which expires in April 2023, for the allocations of the 30 oil and gas blocks in the DRC, spread over five different basins: Cuvette Central, Coastal Basin, Lake Tanganyika, Lake Kivu and Albertine Graben[164]. Initially, the government planned to auction only 16 blocks, but the Ukrainian conflict sharpened Western demands and it was decided to extend it by offering over 240,000 square kilometres of territory, an area the size of Uganda[165].

Of the 30 blocks, three are gas blocks and are located in Lake Kivu; of the remaining 27 – two of which were returned in February 2022 by Ventora Development, one of the companies of the Israeli entrepreneur Dan Gertler[166] – three are located on the coast of the Congo River Basin and nine in the Cuvette Central rainforest region; the other 15 are in the east of the country; two of these cover the Virunga National Park, a sanctuary for endangered dwarf crocodiles and mountain gorillas, on the DRC’s borders with Uganda and Rwanda[167].

In September 2022, a team of researchers visited fourteen villages in four of the proposed oil blocks, and discovered that most of the residents were unaware of the government’s plans[168]. According to Greenpeace’s coordinator for Central Africa, Raoul Monsembula, ‘oil exploration will not make the people of DRC better off: pollution will reach many and revenue will only reach a handful of beneficiaries in Kinshasa and abroad’; of the same opinion are most of the inhabitants of the affected areas, who fear environmental damage[169].

President Felix Tshisekedi’s project aims to boost crude oil production from the current 25,000 barrels per day to 200,000, reassuring that modern drilling methods and strict regulation will be adopted, minimising the ecological impact[170]. There are currently three oil companies drilling in the DRC: Perenco[171], which extracts oil offshore from the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Muanda in Kongo Central, Total, and the Congolese parastatal Sonahydroc[172] (with the support of the UBA DRC bank[173]), which drills in the east of the country[174].

Lake Kivu to be ruined by drilling to extract methane[175]

According to the authorities, the resources that can be found amount to around 22 billion barrels of oil and 66 billion cubic metres of natural gas[176] and would increase the sector’s contribution to the national budget, which currently stands at 6%, up to 40%, thus breaking the dependence on the mining sector, which today accounts for more than 95% of exports[177]. Didier Budimbu certainly has no intention of giving it up: ‘We have the right to benefit from our natural wealth’. According to the minister, the potential reserves covered by the auction could be worth up to USD 1 trillion – although in fact there is no guarantee that any of the blocks will yield as much as envisaged – but he already promises that they will be allocated to the construction of new schools, highways and hospitals[178].

Environmentalists do not believe the President’s reassurances, and are calling on the government to cancel the tender, as the exploitation of those areas would seriously endanger the ecosystem: the extraction activities with the extensive deforestation, the construction of industrial areas, roads, bridges, and infrastructures, besides destroying a precious and delicate floral-fauna balance, would work for the total drying up of the swamps – and water is the lifeblood for the peat bogs; the drilling in the blocks proposed by the government could release 5.8 billion tons of carbon, more than 14% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions: a climate catastrophe[179].

Even from Washington comes the request to withdraw some oil blocks from the tender, those considered more ‘environmentally sensitive’, but the reply from the Minister of Communications Patrick Muyaya is lapidary: the request can only be considered in return for equivalent compensation. Ergo: we have no intention of giving up the economic advantage that the exploitation of the blocks could bring, the environment is not our concern[180]. At the UN Climate Change Conference[181], no one seems to care about the announced havoc, on the contrary: a new agreement is made with the DRC (2021-2031) for the disbursement of another USD 500 million[182], renewing the previous one (2015-2020) of USD 200 million[183]. An oxymoron: money, to counter deforestation, given to those who promote it.

The tender goes ahead and, in January 2023, the Makelele, Idjwi and Lwandjofu methane blocks in the Lake Kivu region are awarded to Canadian and US producers: Idjwi is awarded to Winds Exploration & Production, while the Makelele block is awarded to ReD, a local subsidiary of US-based Symbion Power, whose project includes investments of more than $300m to develop a 60MW gas-to-electricity system to connect consumers in Goma and the North and South Kivu provinces through existing commercial hubs[184]; Alfajiri Energy, based in Canada, has instead secured the Lwandjofu block[185]. As for the allocation of the remaining blocks, there is strict confidentiality.

Protests against the UNO mission in the DRC resulted in the deaths of at least 36 people[186]

In any case, it is clear that the DRC is paying the price of a ‘resource curse’. The recent exponential growth in demand for minerals forces it into a key role that, instead of guaranteeing it a new renaissance, pushes it further and further into the abyss, hostage to all sorts of vultures. The situation in the North-East, thousands of kilometres away from Kinshasa, does not bode well – especially as Rwanda and Uganda, despite Peace Treaties, continue to support rebel militias in North Kivu.

On 24 January 2023, a DRC Sukhoi-25 fighter plane, accused of violating airspace, is targeted by Rwandan anti-aircraft fire: a near-tragedy, the plane returns to the airport unharmed[187]. The incident testifies to the serious tensions between the two countries: for Kinshasa it is a deliberate aggression, therefore an act of war, while Kigali denies having carried it out[188]. The presence of international forces has a counterproductive effect, spreading a feeling of distrust and aversion. The UN peacekeeping operation MONUSCO (deploying at least 17,500 troops since 2010 and costing over USD 1 billion a year[189]), which supports the Congolese armed forces FARDC, is now considered a failure, especially by local communities[190].

Protests against the blue helmets became increasingly heated: in August 2022, hundreds of protesters set fire to mission buildings, causing 36 deaths, including four peacekeepers. Their presence is questioned by Kinshasa, which accuses the UN of fuelling the protests and, on 4 August, expels their spokesman because of his ‘indelicate and inappropriate remarks’, because he said that ‘the UN peacekeepers do not have the military means to defeat the notorious armed group M23’, giving an impression of impotence[191]. Attacks by civilians on peacekeepers continue[192]. The UN Mission assumes that its mandate, which expires on 30 June 2024, will not be renewed.

The seven member states of the Communauté des Etats d’Afrique de l’Est (EAC), of which the DRC has officially been a member since July 2022[193], decide to deploy a regional force in the east: the draft battle plan states that the region is to assemble between 6,500 and 12,000 soldiers with a mandate to ‘contain, defeat and eradicate negative forces’ in the eastern DRC[194]. On 15 August, a Burundian contingent is the first to go into action in the territory, officially marching on Uvira, South Kivu[195]. But one already wonders whether this mission is not yet another costly failure – both in economic terms and in terms of human lives.

The fact remains that the world has no time to look at this immense jungle that is so important for the planet. The government in Kinshasa is unable to truly control its territory, and the majority of the forces on the ground are fine with that. Europe (not France or Belgium, but the Union) should be here, with its diplomatic strength, to offer a counterbalance, but it is not: too busy chasing the madness of populism and neo-Nazism, being blackmailed by Moscow and Washington, desperately looking for the last cell that divides us instead of realising that the only possible future is: together. The same thing applies to African countries, but it is ridiculous to reproach them if we, for one, are incapable of doing so.

FRA028

[1] CABINDA, UNA GUERRA CHE PUZZA DI PETROLIO | IBI World Italia

[2] L’ANGOLA, IL CONGO, LA CINA E LE CITTÀ FANTASMA | IBI World Italia

[3] BOLLORÉ: IL VERO RE D’AFRICA | IBI World Italia

[4] IL FUTURO DELL’AFRICA DIPENDE DAL CONGO | IBI World Italia

[5] https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/04/m23-rebel-group-congo-rwanda-uganda/

[6] https://www.africarivista.it/rd-congo-massacro-a-kishishe-lonu-conferma-luccisione-di-131-civili/210187/

[7] https://kivusecurity.org/about/armedGroups

[8] https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/irc-study-sh+ows-congos-neglected-crisis-leaves-54-million-dead

[9] https://www.caritas.org/2010/02/six-million-dead-in-congos-war/

[10] https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/background-conflict-dr-congo-may-2004

[11] https://kivusecurity.org/reports

[12] https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/democratic-republic-congo-mining-and-minerals#:~:text=2022%2D12%2D14-,Overview,position%20for%20the%20energy%20transition.

[13] https://www.africanews.com/2022/11/03/drcs-artisanal-cobalt-mines-tainted-by-lack-of-compliance//

[14] https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/democratic-republic-of-congo/gold-production

[15] https://www.minerals.net/mineral/columbite.aspx

[16] https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2022/11/4/dr-congos-faltering-fight-against-illegal-cobalt-mines

[17] https://humanglemedia.com/rebels-dr-congo-soldiers-accused-of-illegal-mining-operations-in-fizi-territory/

[18] https://ipisresearch.be/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/1904-IOM-mapping-eastern-DRC.pdf

[19] https://www.raid-uk.org/content/chinese-mining-companies-drc

[20] https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2016/1/19/blood-and-minerals-who-profits-from-conflict-in-drc

[21] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-26946982

[22] https://www.farodiroma.it/dossier-crimini-e-strategie-di-informazione-deviante-complicano-il-puzzle-di-una-guerra-che-ha-moventi-economici-rosati-beltrami-mvuka-vasapollo/

[23] https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/105528/22.pdf

[24] https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/105528/22.pdf

[25] https://orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/ORF_IssueBrief_139_Venugopalan_Final.pdf

[26] https://www.peacewomen.org/sites/default/files/drc_cso_report_2011.pdf

[27] https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/end-mobutus-dictatorship

[28] https://medium.com/@david.himbara_27884/kagame-rewarded-kabarebes-30-year-brutal-service-with-arrest-253bae429fbe

[29] https://www.kcl.ac.uk/rwanda-and-drcs-turbulent-past-continues-to-fuel-their-torrid-relationship

[30] https://www.peaceagreements.org/view/404

[31] https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2009/10/secretary-general-hails-pretoria-agreement-political-milestone-peace

[32] https://2001-2009.state.gov/t/ac/csbm/rd/22627.htm

[33] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2006/11/27/joseph-kabila-vainqueur-officiel-de-l-election-presidentielle-congolaise_839350_3212.html

[34] https://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1855309,00.html

[35] https://www.france24.com/en/20081112-fact-file-conflict-north-kivu-dr-congo

[36] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/766018/DRC_case_study.pdf

[37] https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/04/m23-rebel-group-congo-rwanda-uganda/

[38] https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/12/21/dr-congo-24-killed-election-results-announced

[39] https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/04/m23-rebel-group-congo-rwanda-uganda/

[40] https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/04/m23-rebel-group-congo-rwanda-uganda/

[41] https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/groups-organizations-global-african-history/interahamwe-1992/

[42] https://africacenter.org/spotlight/medley-armed-groups-play-congo-crisis/

[43] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-24849919

[44] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-17689131

[45] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/nov/20/goma-falls-congo-rebels

[46] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2012/10/17/un-accuses-rwanda-of-leading-dr-congo-rebels

[47] https://kivusecurity.org/about/armedGroups

[48] https://www.france24.com/en/20131103-democratic-republic-congo-m23-rebels-declare-ceasefire

[49] https://www.france24.com/en/20131111-democratic-republic-congo-m23-rebels-fail-sign-peace-deal

[50] https://www.dw.com/en/suspected-war-criminal-ntaganda-surrenders/a-16682354

[51] https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/initial-appearance-bosco-ntaganda-scheduled-26-march-2013

[52] https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/07/22/dr-congo-m23-rebels-kill-rape-civilians

[53] https://www.reuters.com/article/congo-democratic-deal-idINDEE9BB0CK20131212

[54] https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/12/04/special-mission/recruitment-m23-rebels-suppress-protests-democratic-republic

[55] https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/12/04/dr-congo-rebels-were-recruited-crush-protests

[56] https://www.dw.com/en/suspected-war-criminal-ntaganda-surrenders/a-16682354 b

[57] https://www.voanews.com/a/explainer-what-s-behind-the-rising-conflict-in-eastern-drc-/6690258.html

[58] https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/disarmament-demobilisation-reintegration-democratic-republic-congo/

[59] https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2022/07/07/Congo-M23-Rwanda-martial-law-demobilisation-ADF-CODECO

[60] https://blog.kivusecurity.org/divisions-between-tshisekedists-and-kabilists-paralyze-the-state-in-eastern-drc/

[61] https://www.radiookapi.net/2019/10/10/actualite/politique/rdc-felix-tshisekedi-annonce-une-derniere-offensive-contre-les-adf

[62] https://www.africanews.com/2021/11/09/dr-congo-military-says-rebels-attack-eastern-base//

[63] https://www.globalr2p.org/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/

[64] https://www.e-ir.info/2023/01/10/opinion-rwandan-support-for-m23-rebels-cannot-continue/

[65] https://thegreatlakeseye.com/post?s=DRC:–Foreign–mercenaries–will–escalate–conflict–in–east_861

[66] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/04/russian-mercenaries-wagner-group-linked-to-civilian-massacres-in-mali ; https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/01/25/russia-wagner-group-africa-terrorism-mali-sudan-central-african-republic-prigozhin/

[67] https://www.ft.com/content/8e720aa2-1cb3-474c-b4eb-805c03504f8f

[68] https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/russian-question-in-congo-conflict-4093620

[69] https://www.dw.com/en/are-white-mercenaries-fighting-in-the-drc-conflict/a-64407711

[70] https://taz.de/Europaeische-Soeldner-im-Kongo/!5904737&s=congo/

[71] https://acpcongo.com/index.php/2022/08/23/fruitful-exchanges-in-moscow-between-minister-gilbert-kabanda-and-the-russian-deputy-minister-in-charge-of-defence/

[72] https://taz.de/Europaeische-Soeldner-im-Kongo/!5904737&s=congo/

[73] https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/news/article/democratic-republic-of-the-congo-great-lakes-region-adoption-of-an-agreement-on

[74] https://edition.cnn.com/2021/12/17/opinions/siddharth-kara-mining-dr-congo/index.html

[75] https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/drc/overview

[76] “Osservatorio di Politica Internazionale” – La Crisi dei Grandi Laghi – (CESI) n° 30 – Maggio 2011 – page 13 https://www.parlamento.it/documenti/repository/affariinternazionali/osservatorio/approfondimenti/PI0030App.pdf

[77] https://www.eisa.org/wep/angoverview2.htm

[78] https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/congo-coltan-cell-phones/

[79] https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/05KINSHASA731_a.html

[80] https://newint.org/features/2004/05/01/congo

[81] https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/africa/april/17/usstake.htm

[82] https://www.union-communiste.org/it/2004-01/congo-ex-zaire-a-country-looted-by-warlords-and-imperialist-companies-1362

[83] https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2022/11/4/dr-congos-faltering-fight-against-illegal-cobalt-mines

[84] https://newint.org/features/2004/05/01/congo

[85] https://reliefweb.int/report/angola/how-kabila-lost-his-way-performance-laurent-d%C3%A9sir%C3%A9-kabilas-government

[86] https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/report-panel-experts-illegal-exploitation-natural-resources-and

[87] “Osservatorio di Politica Internazionale” – La Crisi dei Grandi Laghi – (CESI) n° 30 – Maggio 2011 – page 13 https://www.parlamento.it/documenti/repository/affariinternazionali/osservatorio/approfondimenti/PI0030App.pdf

[88] https://www.parlamento.it/documenti/repository/affariinternazionali/osservatorio/approfondimenti/PI0030App.pdf

[89] https://www.parlamento.it/documenti/repository/affariinternazionali/osservatorio/approfondimenti/PI0030App.pdf

[90] https://landportal.org/fr/node/100425

[91] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/mar/02/looting-machine-warlords-tycoons-smugglers-systematic-theft-africa-wealth-review

[92] https://cdn2.globalwitness.org/archive/files/library/friends_in_need_en_lr.pdf

[93] https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/chap_rep_06_mthembu_salter_200807.pdf

[94] https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Data/Africa_file/Manualreport/cia_09.html

[95] https://7sur7.cd/2021/09/23/rdc-scandale-judiciaire-huawei-condamnee-payer-105-millions-pour-une-licence-imaginaire

[96] https://cdn2.globalwitness.org/archive/files/library/friends_in_need_en_lr.pdf

[97] United Nations Security Council (UNSC), “Interim report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, pursuant to Security Council resolution 1698 (2006)”, S/2007/40, 26 January 2007; UNSC, “Final report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo”, S/2008/43, 13 February 2008; UNSC, “Final report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo”, S/2008/773, 12 December 2008; UNSC, “Final report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo”, S/2009/603, 23 November 2009.

[98] https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/132454/Chinas%20Growing%20Role%20in%20African%20Peace%20and%20Security.pdf

[99] http://www.chinaafricarealstory.com/2015/10/whatever-happened-to-9-billion-china.html

[100] https://cdn2.globalwitness.org/archive/files/library/friends_in_need_en_lr.pdf

[101] https://cdn2.globalwitness.org/archive/files/library/friends_in_need_en_lr.pdf

[102] https://cdn2.globalwitness.org/archive/files/library/friends_in_need_en_lr.pdf

[103] https://www.reuters.com/article/congo-democratic-china-idUKL0989174920080509

[104] https://www.reuters.com/article/congo-democratic-china-imf-idUSLN34513920090323

[105] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/archive/6bn-congo-china-resource-deal-threatened-lack-information/

[106] https://elpais.com/planeta-futuro/

[107] https://news.mongabay.com/2022/05/chinese-companies-linked-to-illegal-logging-and-mining-in-northern-drc/

[108] https://news.mongabay.com/2022/05/chinese-companies-linked-to-illegal-logging-and-mining-in-northern-drc/

[109] https://qz.com/africa/2059378/china-will-punish-its-own-companies-if-they-break-laws-in-the-drc

[110] https://www.citizen.co.za/news/news-world/news-africa/mining-in-drc-halted-after-tension-with-chinese/

[111] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2020/12/23/la-republique-democratique-du-congo-reintegree-dans-l-accord-commercial-avec-les-etats-unis_6064302_3212.html

[112] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-59343922

[113] https://oenz.de/dr-kongo/embezzled-empire-how-kabilas-brother-stashed-millions-overseas-properties

[114] https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/congo-sees-deal-6-bln-china-mining-contract-overhaul-this-year-finmin-2023-01-18/

[116] https://www.aninews.in/news/world/others/dr-congo-new-ground-for-chinese-companies-in-search-of-gold-report20220228021252/

[117] https://www.aninews.in/news/world/others/dr-congo-new-ground-for-chinese-companies-in-search-of-gold-report20220228021252/

[118] https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/metals/120120-chinese-dominance-of-drc-mining-sector-increases-economic-dependence-mines-chamber

[119] https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/bilateral-investment-treaties

[120] https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/africa/central-africa/democratic-republic-congo

[121] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2020/12/23/la-republique-democratique-du-congo-reintegree-dans-l-accord-commercial-avec-les-etats-unis_6064302_3212.html

[122] https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2023.01.13-E-4-Release-MOU-USA-DRC-ZAMBIA-Tripartite-Agreement-Tab-1-MOU-for-U.S.-Assistance-to-Support-DRC-Zambia-EV-Value-Chain-Cooperation-Instrument.pdf

[123] https://www.mining.com/gates-bezos-backed-kobold-metals-to-build-copper-cobalt-mine-in-zambia/

[124] https://www.regenwald.org/themen/staudaemme/grand-inga-ein-weisser-elefant-im-kongo

[125] https://www.mining.com/web/cmoc-pushes-back-as-congos-gecamines-demands-compensation-in-cobalt-mine-dispute/

[126] https://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/The-US-And-China-Are-Rushing-To-Secure-Resources-In-DR-Congo.html

[127] https://www.internationalrivers.org/

[128] https://www.internationalrivers.org/news/international-rivers-statement-on-fortescue-metals-groups-agreement-to-develop-grand-inga-hydro-scheme/

[129] https://www.asso-sherpa.org/perenco-environmental-damage-drc

[130] https://www.greenpeace.org/africa/en/press/52657/the-price-of-oil-extraction-in-dr-congo-is-revealed-ngos-take-perenco-to-court-over-167-pollution-cases/

[131] https://news.mongabay.com/2021/12/the-past-present-and-future-of-the-congo-peatlands-10-takeaways-from-our-series/

[132] https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-27492949

[133] https://www.nature.com/articles/nature21048

[134] https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-biology-of-peatlands-2e-9780199603008?cc=it&lang=en& “The Biology of Peat Bogs” – Rydin, H. & Jeglum, JK – Oxford Univ. Press, 2006 – page 230-233

[135] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02279.x “Global and regional importance of the carbon pool of tropical peatlands” – Page, SE, Rieley, JO & Banks, CJ — Global Change Biology – 17, page 798–818 (2011)

[136] https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-27492949

[137] https://www.greg.gg/webCompSearchDetails.aspx?id=Tq/wnBZlzLc=&r=1&crn=&cn=Centrale%20&rad=ContainsPhrase&ck=False?height

[138] https://g1.globo.com/rs/rio-grande-do-sul/noticia/desembargadores-negam-pedido-de-suspeicao-de-ex-diretor-da-petrobras-contra-moro.ghtml

[139] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/01/brazil-operation-car-wash-is-this-the-biggest-corruption-scandal-in-history

[140] https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/280/

[141] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/drc-congo-oil-national-parks-gorillas-virunga-salonga-endangered-special-mountain-a8336286.html

[142] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/oil-gas-and-mining/null-and-void-comicos-oil-aspirations-in-drc/

[143] https://redd.unfccc.int/uploads/3262_4_redd_investment_plan_eng.pdf

[144] https://news.mongabay.com/2022/10/locals-in-the-dark-about-oil-auctions-in-drc-report/

[145] https://cases.open.ubc.ca/w17t2cons200-25/

[146] https://www.rainforestfoundationuk.org/fr/le-gouvernement-de-rdc-suspend-une-societe-forestiere-apres-la-denonciation-par-la-societe-civile/

[147] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/press-releases/le-gouvernement-de-rdc-r%C3%A9tablit-des-concessions-foresti%C3%A8res-ill%C3%A9gales-en-violation-de-son-propre-moratoire/

[148] https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/4475301-14-Concessions.html

[149] https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/historic-agreement-signed-protect-worlds-largest-tropical-peatland#:~:text=The%20Brazzaville%20Declaration%20aims%20to,peatlands%20%E2%80%93%20and%20the%20Congo%20Basin.

[150] https://www.climatechangenews.com/2018/05/24/norway-loggerheads-dr-congo-forest-protection-payments/

[151] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/mar/31/destruction-of-worlds-forests-increased-sharply-in-2020-loss-tree-cover-tropical

[152] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/feb/28/ridiculous-plan-to-drain-congo-peat-bog-could-release-vast-amount-of-carbon-aoe

[153] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/press-releases/congo-oil-project-obtained-by-corruption-risk-magnate-threatens-climate-critical-peatland-forest/

[154] https://congopeat.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/49/2022/07/CongoPeat-Briefing-on-Oil-Exploration_published.pdf

[155] https://afrique.latribune.fr/les-exclusifs/cercle-de-pouvoir/2019-11-12/classement-forbes-des-milliardaires-africains-francophones-willy-etoka-dans-le-top-10-832859.html

[156] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/press-releases/congo-oil-project-obtained-by-corruption-risk-magnate-threatens-climate-critical-peatland-forest/

[157] https://www.africaintelligence.com/central-africa/2018/07/04/claude-wilfrid-etoka-sassou-nguesso-s-leading-advocate,108315820-art

[158] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/forests/what-lies-beneath/

[159] https://www.africarivista.it/rd-congo-allasta-blocchi-petroliferi-anche-in-zone-protette/204886/

[160] https://www.ft.com/content/5ea6f899-bb55-478f-a14a-a6dd37aae724

[161] https://www.ft.com/content/5ea6f899-bb55-478f-a14a-a6dd37aae724

[162] https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/forests/what-lies-beneath/

[163] https://redd-monitor.org/2020/04/08/oil-corruption-and-lies-in-the-republic-of-congo/

[164] https://hawilti.com/energy/upstream/d-r-congo-opens-new-bid-round-for-30-oil-gas-blocks%EF%BF%BC/

[165] https://www.africanews.com/2022/07/19/drc-expands-oil-and-gas-blocks-put-up-for-auction//

[166] https://www.theafricareport.com/228358/drc-eni-totalenergies-exxon-whos-ready-to-fight-for-congolese-oil/

[167] https://www.independent.co.ug/dr-congo-auctions-30-oil-and-gas-blocks/

[168] https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-africa-stateless/2022/09/38e752f8-oil-blocks-report-english-v1.2.pdf

[169] https://news.mongabay.com/2022/10/locals-in-the-dark-about-oil-auctions-in-drc-report/

[170] https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/congo-oil-blocks-auction-draws-warnings-environmental-catastrophe-2022-07-28/

[171] https://www.perenco.com/

[172] https://www.monrespro.cd/entreprise/sonahydroc/

[173] https://www.ubardc.com/2022/07/19/sonahydroc-s-a-et-uba-rdc-s-a-signent-une-convention-de-financement-de-13-millions-de-dollars-americains/

[174] https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/democratic-republic-congo-oil-nd-gas

[175] https://www.explorerwandatours.com/rwanda-tours/3-days-lake-kivu-visit.html

[176] https://hawilti.com/energy/upstream/d-r-congo-opens-new-bid-round-for-30-oil-gas-blocks%EF%BF%BC/

[177] https://www.theafricareport.com/228358/drc-eni-totalenergies-exxon-whos-ready-to-fight-for-congolese-oil/

[178] https://www.ft.com/content/5ea6f899-bb55-478f-a14a-a6dd37aae724

[179] https://www.independent.co.ug/dr-congo-auctions-30-oil-and-gas-blocks/

[180] https://copperbeltkatangamining.com/withdrawal-of-certain-oil-blocks-from-calls-for-tenders-request-of-united-states-can-only-be-taken-into-account-following-equivalent-consideration-patrick-muyaya/

[181] https://ukcop26.org/the-conference/cop26-outcomes/

[182] https://www.cafi.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/EB.2021.18%20-%20Letter%20of%20Intent%20with%20the%20DRC%202021-2030%20with%20annexes.pdf

[183] https://www.cafi.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/LOI%20V7%20Final%2018%20April%202016%20-ENG%20-%20with%20logos.pdf

[184] https://energychamber.org/aec-backs-drc-move-to-choose-symbion-power-to-develop-biogas-to-power-in-the-drc/

[185] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/congo-awards-lake-kivu-gas-blocks-us-canadian-producers-2023-01-17/

[186] https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20220804-drc-expels-monusco-spokesman-over-deadly-anti-un-protests-in-eastern-kivu-provinces

[187] https://edition.cnn.com/2023/01/25/africa/drc-rwanda-govt-tensions-intl/index.html

[188] https://edition.cnn.com/2023/01/25/africa/drc-rwanda-govt-tensions-intl/index.html

[189] https://www.africarivista.it/le-missioni-di-peacekeeping-in-africa-e-il-caso-della-rd-congo/206936/

[190] https://www.civicus.org/index.php/media-resources/news/interviews/5983-drc-the-united-nations-peacekeeping-mission-has-failed

[191] https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20220804-drc-expels-monusco-spokesman-over-deadly-anti-un-protests-in-eastern-kivu-provinces

[192] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/civilians-attack-un-peacekeeping-convoy-eastern-congo-2022-11-02/

[193] https://www.radiookapi.net/2022/07/11/actualite/politique/la-rdc-devient-officiellement-membre-de-leac

[194] https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/east-africas-dr-congo-force-case-caution

[195] https://7sur7.cd/2022/08/15/eac-un-contingent-burundais-entre-officiellement-au-sud-kivu-pour-traquer-les-groupes

Leave a Reply