ENERGY TAXES AND THE CRISIS OF DEMOCRACY

Democracy is on its knees. Those who have it ignore it and do not participate in it, those who do not have it die on the barricades demanding it in vain from increasingly inhuman and pragmatic regimes. The modern individual revels in his own selfishness, and does not realise that he now has chains around his neck – the ones envisaged by the dystopias of 20th century science fiction and which, until recently, seemed unattainable to us: precisely science fiction.

On the morning of mid-August, the German federal government decided on an energy price levy of more than 2 cents per Kwh. This special tax is necessary to prevent the entire energy industry, which is caught in the noose of soaring hydrocarbon prices due to the war in Ukraine, from going bankrupt by autumn. For households, according to government calculations, the cost of electricity will rise by almost €500 per year, and things could get even worse if the war does not end. No one can yet calculate how much the costs of gas used by companies and households will rise, but these will be very difficult surprises to overcome, and will reach households at the latest in the final count of the year.

The governing coalition has little room for manoeuvre. One could tax the oil industry’s crazy increases in earnings – something that would be socially justifiable and desirable, and which is being proposed by the Greens and the Socialist Left. But the FDP Liberals are against it, and without their vote, this proposal will not pass. Needless to ask what the Christian Democrats, who see the possible goal of bringing down the federal government in the war in Ukraine and thus provoking extraordinary elections and ‘avenging’ the bitter defeat of a few months ago, think. If a vote were taken today, the SDP would be humiliated and the CDU would return to the Chancellery with fanfare.

The issue concerns all countries of the world, and thus also all Western democracies. In Italy, gas price increases of 45% and electricity price increases of 15% are calculated – price increases that are almost entirely covered by the state coffers and an increased debt that could amount to EUR 20 billion: without this measure, gas bill increases would be 91% per household on electricity and 70% per household on gas. With Italy in an election campaign, any other decision would have compromised the hopes of the party taking responsibility to disappear from Parliament – especially given the extreme fragmentation of the electoral framework and the swarming of acronyms.

All this would have been different if the European Union had already started investing 20 years ago, consistently in renewable energy; if all allies, Germany in the lead, had not become dependent on the low prices offered by Russia, which are now like a trap in which we are hopelessly caught; if the sanctions against Russia had worked as a deterrent and had forced Moscow to stop the massacre in Ukraine. Things that did not happen. My grandfather used to say: if my uncle had wheels maybe he would be a tram. We have to ask ourselves why they didn’t happen, and I see two main reasons. First: until the war unleashed by Putin, we all gained from it – and industry most of all, since the climate emergency is talked about but to make ourselves look good on TV. Facts: almost none. Second: Western governments are convinced (probably rightly) that any reduction in household welfare means an irreparable electoral blow.

Translated into current terms: the EU has imposed sanctions on Russia, and these, so far, have not stopped the war. Western families, moved to compassion by the tragedy of the Ukrainians, have agreed to take on more than 5 million fugitives. Sanctions do not achieve the desired result for two reasons. The first: Putin can impose any measure on his citizens – in Russia, anyone who protests ends up in jail or with a bullet in the head; in democracies, on the other hand, fortunately, no one can impose such prices without there being a vehement street protest and a radical change in the electoral orientation of the citizenry. Second reason: we have accepted the sanctions proposal made by NATO (and, frankly, I don’t see any acceptable alternative), but many economically strong nations, China in the lead, continue to trade with Moscow and earn big money from Western sanctions.

The world is starving, because Ukrainian grain no longer arrives. Europe is freezing, because the hydrocarbons coming from the pipelines running through Ukraine are almost at a standstill. The entire planet is burning or drowning because of the consequences, more frightening every year, of climate change. For the first time in 75 years, Europe is once again the theatre of war, and in every home there come, distinctly, the echoes of missiles hitting Ukrainian cities and frightening the conscious part of our population: all it takes is one serious incident, and we will all be at war.

On this issue too, China, Russia and the USA can impose war on their own citizens and stifle any critical reaction, while the EU, if it did so, would have to reckon with the outbreak of mass hysteria with incalculable effects – exactly what Putin is speculating on in pursuing his feral inhuman project.

It proves what has unfortunately always been known: citizens of countries humiliated by dictatorial regimes demand freedom, the right of expression, and are often willing to die to obtain it. Citizens of democratic countries believe in selfishness, not solidarity, and consider freedom an ancillary function of welfare, which they enjoy by birth and which they also believe they have the right to abuse. The victims of regimes are politically aware (just look at the incredible battles of the people of Hong-Kong), the children of welfare don’t give a damn. The result: parties in the West no longer have parties that consistently pursue a line and feed off the active contribution of the citizens, but are mere electoral offices that dispense bribes. If these do not come, the electorate votes for something else.

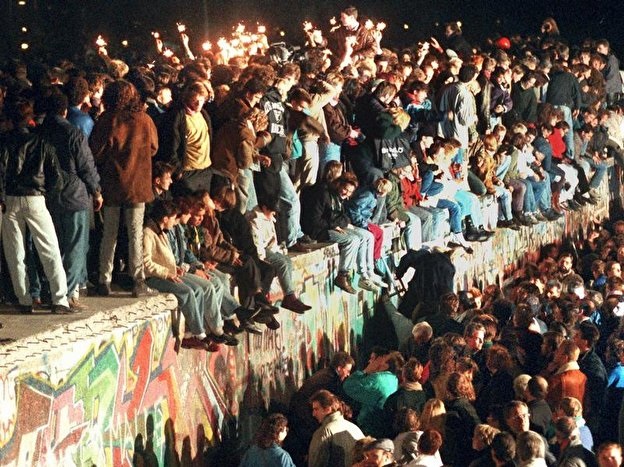

The most painful example I remember is that of the Fall of the Berlin Wall. In the preceding months, tens of thousands of GDR citizens had participated in marches, prayer evenings, deep political discussions, and different political tendencies had gathered around a Round Table of democrats, whose goal was to bring freedom and democracy to the GDR. A few minutes after the Fall of the Wall, all this was forgotten: hundreds of thousands of GDR citizens accepted the occupation and economic exploitation of the BRD, forgetting all the politicisation and struggles that had driven the libertarian movement until an hour before.

The weakness of democracy lies precisely in the fact that the vast majority of citizens live it unconsciously and adhere to nothing except what they perceive as their own immediate benefit. This is why, today, sanctions against Russia, like the restrictive measures imposed because of the pandemic, come up against increasingly substantial groups of citizens who demand the right to actively dissent. For this reason, imposing sanctions on Russia, which is a just, necessary and rightful measure, will become highly unpopular, and will carry significant electoral weight, as soon as citizens feel they have to pay out of their own pockets. In the United States, to avoid this, a climate of violence, ghettoisation, misery and fear prevails – and at the helm is a very weak government that does not really know what to do.

The American Empire is undergoing the same irreversible decadence as the Roman Empire. The Barbarians are at the gates, and they are not coming from North Africa, as the most naïve ones under the Europeans fear, but from the East, as it has always been. We Europeans still have the chance to take destiny into our own hands and choose a different path – one of solidarity, unity and resistance, one that gives Putin no hope. Unfortunately, we do not have the politicians necessary for this task. As for Giuseppe Mazzini, today, nobody even knows who he is anymore and I am sure that if you ask the average child who led the government of the free Roman Republic, the answer would be only one: Francesco Totti.

GER025

Leave a Reply